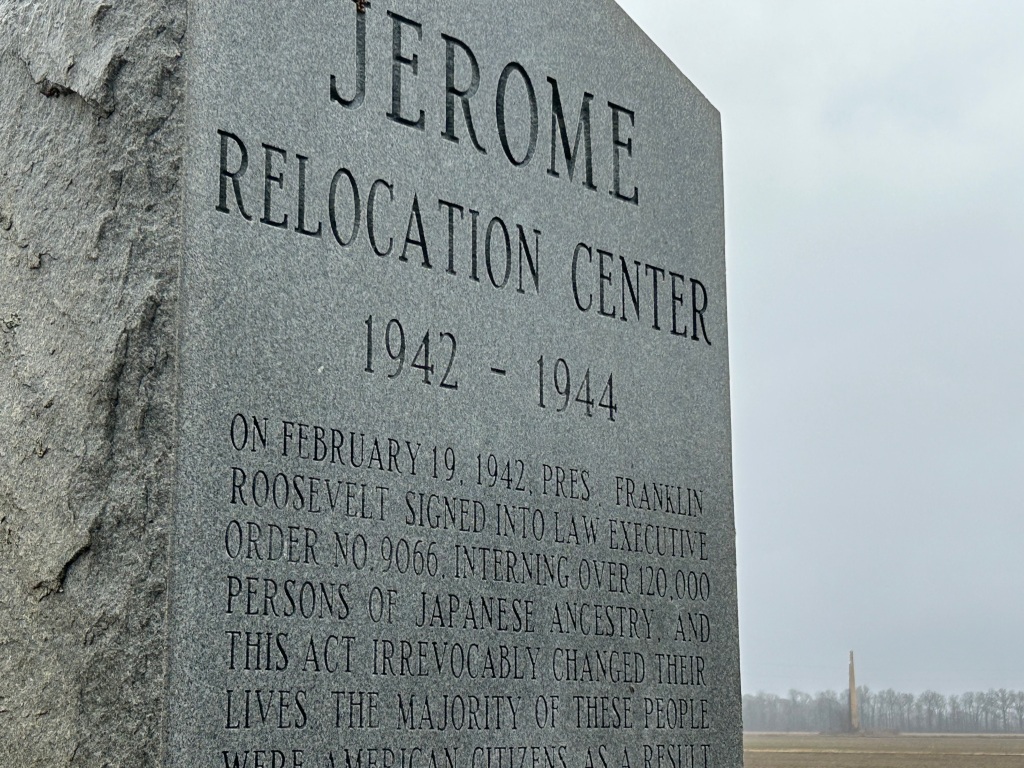

The day after Pearl Harbor, an angry FDR called it ‘a date which will live in infamy’, and he began to restrict the rights of Japanese Americans. First there was a curfew, then bank accounts were seized overnight, businesses shuttered, homes were searched, guns were collected, cameras and radios were taken, Japanese language schools were closed, and travel was restricted. US citizens of German and Italian descent were free to live their lives, but US citizens of Japanese descent were not. Then, at noon, on 30 March 1942: any person of Japanese descent found on Bainbridge Island—opposite Seattle—would be arrested and charged as a criminal. Families were given short notice, allowed two small bags—or one and a baby—, and were sent to the state fairground at Puyallup—near Tacoma. Barbed wire fences and armed soldiers surrounded the ‘assembly centers’. There, they were lined up by family, with their family number tags tied to their clothes, oldest in front, youngest in back.

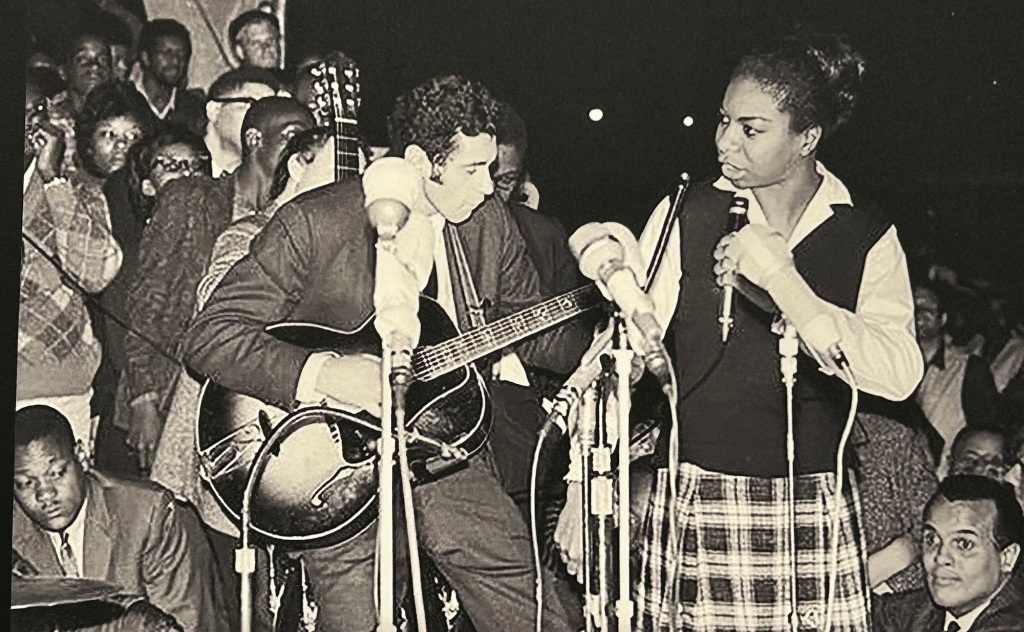

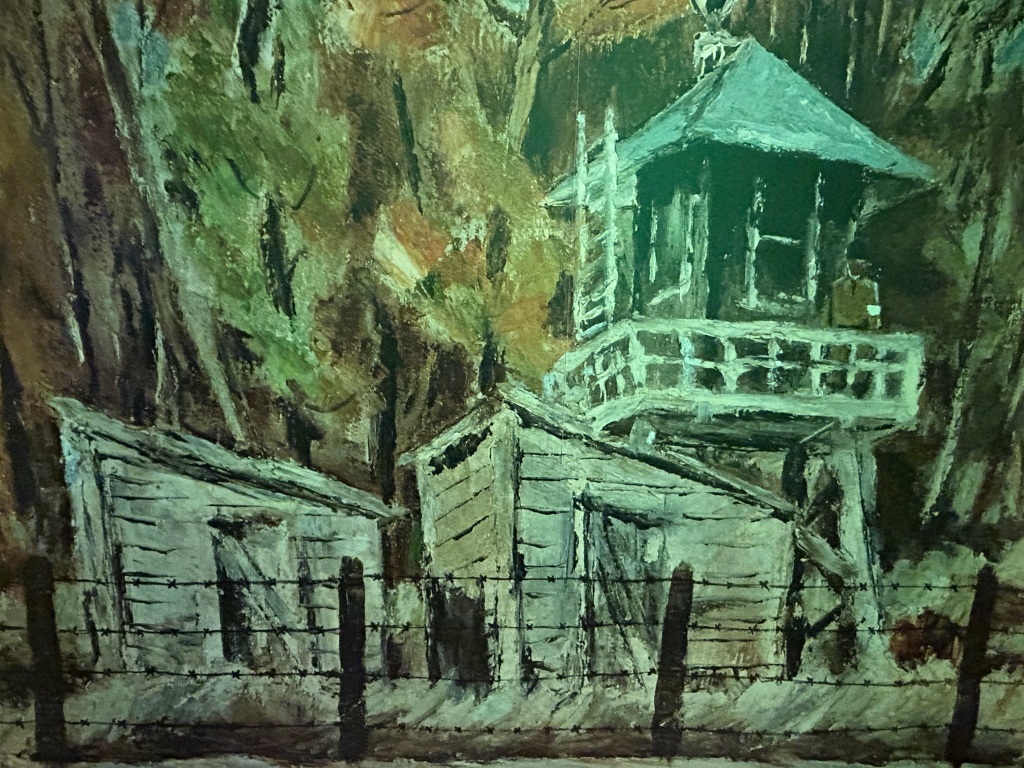

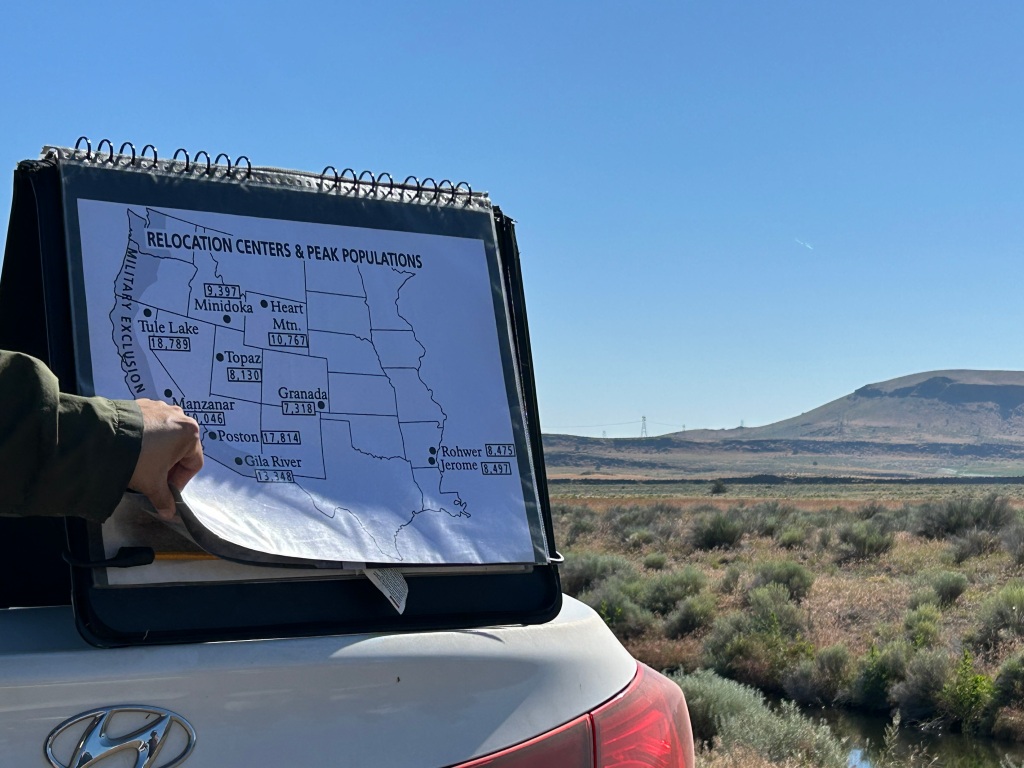

San Francisco residents went to Tanforan—now a shopping mall on the peninsula. Los Angeles residents were sent to Santa Anita or Pomona. Some were housed in racetrack horse stalls, which they needed to clean out themselves. California and half of Washington, Oregon and Arizona were declared ‘exclusion zones’ by the military, and no person of Japanese descent was allowed to remain there. Instead, they were transported from the assembly centers to one of ten camps. The American woman and her baby above were sent to Manzanar in California and then to Minidoka in Idaho. Others went to Amache in Colorado, Rohwer & Jerome in Arkansas, Topaz in Utah, Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Poston & Gila River in Arizona, and some were sent to the ‘segregation camp’ at Tule Lake in California near Oregon. Some male inmates were ordered to build their own barracks, latrines and other buildings. Women prepared meals for thousands. Guard towers were raised along barbed wire fences with searchlights and machine guns pointed inward. There was no privacy, not among family, not at meals, not in the group latrines and not in the group showers. The camps were in remote, desolate, dusty, unpopulated areas away from towns, many were deserts, some mountains and all were sabishii—lonely and forsaken.

Many Americans, including those incarcerated, were lied to about the program by our government: “temporary”, “for your own safety”, “normal” and “happy”. Even today, the program is referred to as “Japanese Internment Camps”, but the vast majority of those incarcerated were not Japanese, they were US citizens, mainly by birth, many never having been to Japan. Propaganda films lied and stated that “household belongings” were shipped to “pioneer villages”, that only those “within a stone’s throw” of military bases were forced to move, that people were “given jobs and more space in which to live” and “managed their own security”. The program was sold as being exemplarily generous, that the military provided for all needs and that the Japanese Americans “approved whole-heartedly”. Journalists and others were periodically given limited access only to the barracks of the most cooperative inmates.

In fact, there were water shortages, food shortages, food poisoning, unsafe living and working conditions, military brutality, unfair punishments, false charges, and inmates fatally shot, including a dog walker at Topaz, a truck driver at Tule Lake, and two protesters at Manzanar where guards fired into a crowd. Some elderly patients had been taken to the camps from their hospital beds, and over 1,850 died of disease and medical problems, including many infants. Complaints were discouraged or mocked. Pressure campaigns were used to enlist men into active combat in Europe. And always, anyone suspected of being disloyal was encouraged to renounce their citizenship and leave the country. In this system, particularly at Tule Lake, some reacted to their treatment by trying to be more Japanese, organizing protests and yelling Banzai—‘long live the Emperor’—at the guards.

They were Americans, and their Constitutional Rights of speech, to be secure in their homes and to due process were all violated for years. The root of this program was racism. Americans of Japanese descent were assumed to have loyalty to a foreign power, and even when they were natural born American citizens, they couldn’t be trusted and would have to prove their loyalty again and again. The Issei—1st generation—chose this country rather than the one of their birth. The Nissei—second generation—were born here, but some parents sent their children back for schooling Japan to preserve their language and culture. These children were called Kibei—returnees to America—, indicating that their parents wanted them to live here. All were Americans, either by their own choice or by their parents’. Only their fellow citizens refused to see them as truly Americans.

Although I quote Eleanor Roosevelt below, FDR and many other Americans believed in the ‘melting pot’—meaning melting metal to forge steel—, that Americans had a duty to assimilate and that their cultures would be purified into one culture. But the price of citizenship does not include giving up one’s culture, whether your name is Ohara or O’Hara. Imagine something happens in the future, and people of your family background are herded up and sent to Guantanamo. Even though you did nothing wrong, your guilt is suspected based on your family cultural background. Your communications are censored, and you are treated the same as foreigners or prisoners of war. And when you finally are freed, all your property has been taken, and nobody will help.

Visit national park sites for camps like Manzanar, Minidoka, Amache and Tule Lake, and interpretive sites in Seattle like the Klondike visitor center which partners with Bainbridge Island and the Wing Luke Museum. Topaz has a museum in Delta Utah (off I-15 towards Great Basin). Poston (off I-10) has a historic marker placed by internees & the Colorado River Indian Tribes near Parker on the Arizona border with California. Heart Mountain has an interpretive center between Cody and Powell in Wyoming (on the road between Yellowstone and Bighorn Canyon). Gila River is on restricted reservation land near Hohokam Pima—neither are open to the public—but the Huhugam Heritage Center has a small free exhibit, not far from Phoenix. There’s a museum in McGehee Arkansas for Rohwer and a monument for Jerome; both are just south of Arkansas Post. The Hawaiian experience was very different, but Honouliuli will eventually open as a historic site. Please encourage your elected representatives to preserve the history at all the camps.

I encourage you to read more about the experiences of the Americans who were sent to American Concentration Camps during WWII: Farewell to Manzanar, Only What We Could Carry, Journey to Topaz, Snow Falling on Cedars, and They Called Us Enemy, among many others. And take a moment to think about how you would feel, if it happened to your family.

“We have no common race in this country, but we have an ideal to which all of us are loyal:

Eleanor Roosevelt, after visiting Gila River during WWII

we cannot progress if we look down upon any group of people amongst us

because of race or religion.

Every citizen in this country has a right to our basic freedoms,

to justice and to equality of opportunity.

We retain the right to lead our individual lives as we please,

but we can only do so if we grant to others the freedoms that we wish for ourselves.”