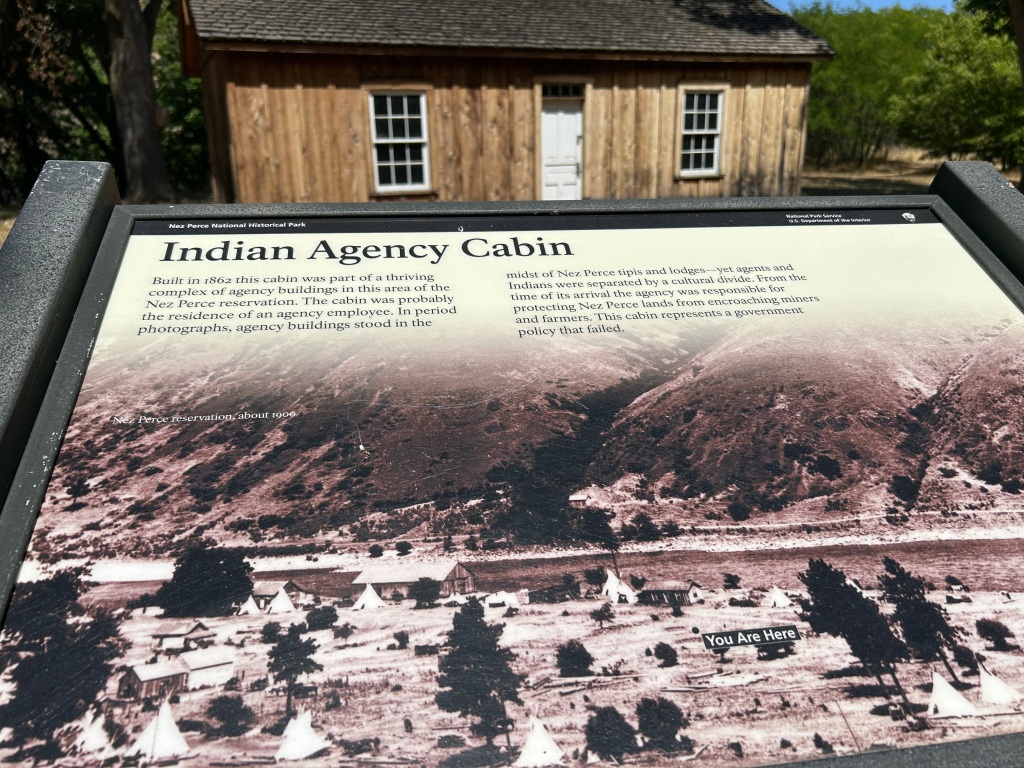

The visitor center in Idaho is on a hill above where the Lapwai Creek flows into the Clearwater River, which joins the Snake River a few miles downstream in Lewiston. The river banks were an excellent place for salmon, berries, edible flowers, and game, and the Nimiipuu used to arrive in the fall and stay through winter. By summer, they would be hunting up in the hills, forests & mountains. French trappers called the tribe Nez Perce or ‘Pierced Nose’, although that wasn’t a traditional tribal practice. When Lewis & Clark passed through, the Nimiipuu assisted the expedition and helped them make canoes. When the missionaries and other settlers arrived, they were forced to change. Many tried desperately to compromise and adapt. After the nearby Whitman mission ended in a massacre, racist demagoguery fueled far more excessive violence across the west, bringing the US military, war, exile and restricted reservation life, including here around the Spaulding mission, pictured circa 1900.

The affiliated Nez Perce National Historic Trail, which marks the flight of the tribe from the US Army, is now part of the broad official Nez Perce NHP, including Big Hole in Montana, a refuge near Lake Roosevelt, the White Bird & Clearwater Battlefields, through Lolo Pass, Yellowstone, Billings and up to Bear Paw Battlefield. Over the years, I’ve visited these places on roadtrips, read several of the books, from I Will Fight No More Forever to Chief Joseph & the Flight of the Nez Perce and pondered the mistakes and tragedy. There is simply no excuse for breaking treaties, stealing land, or killing defenseless people, including women, children, the elderly and infants. When leaders take advantage of popular anger to focus attacks against a community, the result is often far more evil than any original sins. I encourage you to learn more, since the problem of demagoguery is still with us.

But the Nez Perce tribe is still here with us, like the flowers they used to cultivate here. They are re-learning the language that they used to be punished for speaking. They self-govern, petition the US government, sing songs, dance, teach their kids to gather plants, hunt, fish and carry on their cultural traditions and exercise their treaty rights. The lessons of their forefathers and their oral traditions continue to be remembered, spoken aloud and passed down to future generations. The park preserves petroglyphs, artifacts and sites of mythology. Their culture is vibrant and contributes a valuable perspective to all of us. They are not doomed to be permanent prisoners of tragedy, and the park film here is a refreshing reminder of the resilience and life of their culture and of the human spirit.