Favorite photos & videos from my recent trip to Baja!

UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Mexico

The highlight of my trip to Baja California last month was seeing Gray Whales (see videos below) in the Ojo de Liebre—hare’s eye—Lagoon, in the northeastern corner of the huge Vizcaíno biosphere and world heritage site in central Baja. I must thank the legendary Shari Bondi for organizing the experience, as there’s an element of magic required to bring people and whales together well. Unlike any whale watching experience I’ve ever had, the gray whales can be quite friendly. One female approached my boat, stuck her nose up and touched my hand.

The rock art mountains are also within the Vizcaíno preserve, along with several other lagoons popular among winter-breeding gray whales and turtles. Since the lagoons are closely regulated, the only way to see these whales is to join a tour. Since the winter season is short, the tour guides typically work with local hotels and add lagoon-side camps. You may find it difficult to book a room in Guerrero Negro around February, unless you book a package tour. Some visitors spend days on site, taking multiple whale watching trips. Enjoy!

The full name of the world heritage site is ‘Islands and Protected Areas of the Gulf of California’, and the UNESCO site covers much of the old Sea of Cortez which Jacques Cousteau once called ‘the world’s aquarium’. Many of the mountainous islands in the gulf are home to unique species—including a rattle-less rattlesnake—and are protected from development, including the island of Espíritu Santo near La Paz. Last month I visited many of the gulf’s bays on the Baja peninsula, including Bahías de Los Ángeles, Concepción, Loreto and La Paz. In the Loreto national marine park, I saw bottlenose dolphin and fin, humpback and blue whales, including those blues in the videos below.

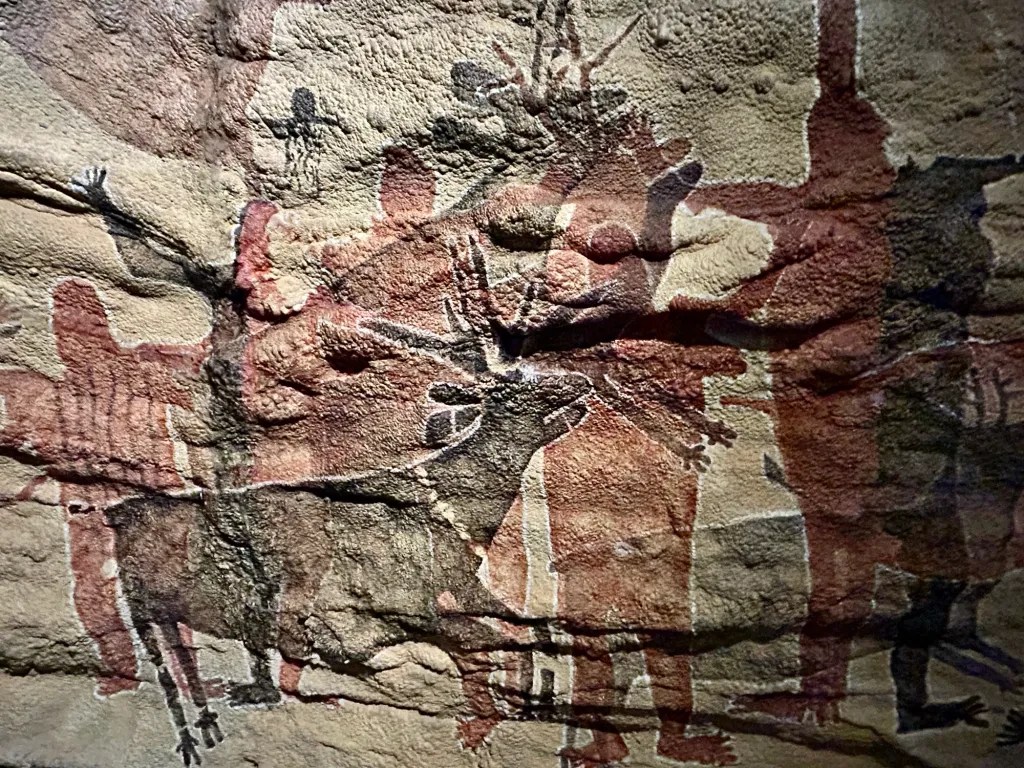

Earlier this month I visited Sierra de San Francisco in central Baja Mexico to see the prehistoric rock paintings which are a world heritage site. They are spread out over a vast, mountainous area and just to see a few requires a 5 day group trek on burro to reach several different caves. One closer site, El Ratón—called ‘the rat’ but meant to be a cougar—, is a short hike off a long, well-paved road. Unfortunately, it’s not the best of the rock paintings, as the alcove is fairly open and the art has faded. The small free museum in San Ignacio is overseen by an official who provides required passes out of his office next door, when he’s there. Hiring a local guide is required along with paying various government fees. For a solo Baja driver, it’s best to visit El Ratón on the way back north, as the cave road is north of San Ignacio, where you must pay first. Group tours can be reserved from San Ignacio, Loreto, and Guerrero Negro. Frankly, I recommend just going to the museum and making a donation. There you can see some good photographs of several of the best examples, along with a large reproduction, above, to give you a sense of how they are displayed on alcoves and in caves. Traveling through Baja, you see reproductions in many public spaces, proudly reflecting the internationally renowned 2000 year old cave art, the cultural remnants of the Cochimí people.

Earlier this month, I visited El Pinacate y Gran Desierto de Altar [literally ‘the stink beetle and the great high desert’]. It’s a UNESCO Biosphere and World Heritage Site in Sonora Mexico, and it’s a sister park to Organ Pipe Cactus NM across the border in Arizona. A dozen pronghorn scampered through the various cactus, but unfortunately the border wall prevents many species from moving freely in their natural habitat. The main attraction is ten large volcanic craters, including the deep, symmetrical Elegante below. The landscape is extraordinary and otherworldly, with long black lava walls, cinder cones, sand dunes, various cacti, bushes, shrubs and wildflowers. There is enough rainfall to support birds, reptiles and wildlife like big horn sheep. Some folks camp overnight to experience the vast dark skies, far from large human settlements.

A 2018 movie called Sonora was filmed here, and the movie describes the desert as both the middle of nowhere and ‘the devil’s highway’. A few years ago some criminals moved into the area, but they are gone now. The roads are severely washboarded, sandy and sometimes are blocked by local landholders due to disputes over compensation, so I hired a driver, a van and a guide. There are no facilities to speak of, so you need to bring whatever you need in and pack everything out. From the supercharger in Gila Bend, it’s more than a full charge round trip to Puerto Peñasco or Rocky Point where guided tours depart, so I charged at my hotel on the Playa Bonita. The local economy is still recovering from various border shutdowns and Covid, but the onsite park museum is expected to reopen soon, which will bring more visitors. But for my visit, I was happy to have the whole park to myself.

To visit 16 of Mexico’s World Heritage Sites in a zero emission vehicle, I drove round trip from Texas to Mexico City, through 13 Mexican states, and, while a bit bumpy, I enjoyed the trip very much. All my trip report links are at the end of this post.

If you read online comments in the US, you might get the idea that traveling in Mexico is impossible or foolhardy at best. Well, you can’t believe everything you read online (except this blog of course). Over the entire trip, I was only asked for one ‘bribe’ of $1, to park briefly in a student parking lot without a student id. The state police, national guard and military were all very professional and waved me through either without comment or after glancing at my car permit. While I saw crime on the TV news in Mexico, I observed none.

After driving in Mexico, I finally understand driving in Texas. Instead of overpasses, underpasses and clover leafs, just use ‘retornos’ or U-turns. Folks leave the nice highways, well, they’re on their own, immediately. Want to slow traffic, without relying on folks to obey signs? Just use lots of speed-bumps or topes. Although, there are even more techniques to learn. First, always be alert. Pothole! Second, drive halfway in the breakdown lane to avoid head-on collisions with oncoming passing traffic. Third, always be alert, seriously, you need to pay attention and think while driving. Drivers are generally nice, but get out of the way of speed demons and quickly pass vehicles that wouldn’t be allowed on the roads in the US.

All Mexico is divided into three parts. Mexico City is best navigated by metro, with its one way streets, traffic and lack of parking. Traffic can be stultifying. Of course, electric cars are exempt from the Hoy No Circula—‘no driving today’—restrictions, which otherwise limit your access to the city according to the last character of your license plate. Circumnavigating the city on the ring road requires tolls: take your ticket and be prepared to pay cash (although a few places take credit cards). Remember the metro is 5 pesos or ~30 cents.

The mid-sized cities and tourist areas outside Mexico City are still crowded, but passable by private car. I was frequently fortunate to find parking very near World Heritage Sites in mid-sized city centers. Of course, the more touristy, the more likely that the roads are cobblestone. San Miguel de Allende may be magical, but I scraped the bottom of my car several times on medieval stones. Better to park outside the historic zones and walk. Still, driving your own car gets you to places that are otherwise challenging to reach.

And then there are the mountains and remote villages. Ah, lovely! But no signal to navigate. I got lost three times near the butterfly reserve. Once, my navigation asked me to drive between two trees on each side of a hiking trail. But I must admit, some of the most beautiful places in Mexico are just off the grid. Horse-driven ploughs, indigenous costumes, and forest-covered volcanoes await. Long drives are best on toll roads with frequent $5 to $15 tolls.

On this trip, I used Superchargers exclusively, and I only saw half a dozen Teslas in Mexico, including my own, mostly at chargers. Unlike the US, there isn’t a government subsidy for most electric cars, so my car was not just unusual, but uneconomical in the short run. I got few comments or looks, and the valet parking attendants had never driven one before (and didn’t like them). There are a few other electric models that I saw on TV, which we don’t have in the US, and I spotted a few of those in Mexico. But overall, electric cars are an elite affair, with parking and charging in the most expensive malls in expensive neighborhoods. I found the supercharger network from McAllen to Puebla accessible and without gaps, although it’s better to charge whenever you can, just in case you need a lot of air conditioning or have to detour.

While Mexico might seem intimidating or unrefined, the truth is that it’s worth the trouble. There are European-style cathedrals, ancient pyramids (photo from Anthropology Museum), glorious art, scrumptious food, and natural wonders that are well worth driving a couple days with the trucks on the long highways. An unexpected side benefit to driving was passing through three UNESCO Biospheres along the way: Cumbres de Monterrey, La Primavera near Tequila, and Los Volcanes near Mt Popocatépetl. I reviewed the State Department warnings and used them to plan my trip, but, again, the best way to avoid crime is to avoid drugs and be careful. Americans should take advantage of the wonderful travel opportunities just south of our border, and I’m not talking about all-you-can-whatever resorts that you fly into. See the real Mexico, and drive electric!

Welcome to Mexico! Above is the statue of Miguel Hidalgo y…

Above is one of a half dozen side chapels in…

On the right is the Alhóndiga, an old grain exchange,…

UNESCO recognizes this colorful, artistic city for its historic zone…

Feathered and fire serpents adorn the steps of the Quetzalcóatl…

OK, it’s not a solar eclipse, but this 450+ year…

The volcano Popocatépetl was active, unleashing a huge cloud of…

Butterflies are free. Monarchs may arrive at their winter home…

The city’s cathedral with its famed tall towers (above) is…

If you were disappointed by not being able to climb…

This is only half of a World Heritage Site, Mexico…

University City, the main campus of UNAM, the National Autonomous…

In the US, the Independence War means the same as…

The Plaza Santo Domingo in the historic center of Mexico…

Luis Barragán was an architect from Guadalajara around 1930, after…

I arrived at this World Heritage Site on Sunday late…

Full disclosure: the three houses here were being renovated the…

Originally designed to be a hospital, like Les Invalides in…

Technically, the name of this UNESCO World Heritage Site is…

Technically, the name of this UNESCO World Heritage Site is Agave Landscape and Ancient Industrial Facilities of Tequila. But that’s a mouthful. For at least 2,000 years, folks around here have been making pulque, a milky agave wine. A wealthy Spanish aristocrat, working around a royal ban on new vineyards, started distilling blue agave, inventing a new drink named after the town of Tequila in Jalisco state. Above are Tres Mujeres oak barrels aging tequila for years, to the sound of classical music, which is thought to improve the taste.

But wait, trendy folks claim they don’t like tequila and only drink mezcal, which is silly since tequila is a type of mezcal. Mezcal is a very broad category of alcohol, including home brews, stuff sold in plastic containers out of the trunks of cars, and a few quality refined spirits, like tequila. Some mezcals use extra wood burning to add more smoke flavor, but good tequila just uses the cooked agave fruit and the smokiness from the barrel. Some tequilas add food coloring, but good tequilas similarly gain their color naturally.

Another misconception is that like champagne, all tequila must be made near Tequila in Jalisco. That’s not true. Tequila can be made anywhere in the state of Jalisco and also in designated areas of half a dozen other states in Mexico. We did a tequila tasting many years ago out of Puerta Vallarta, and it was as authentic and delicious as the ones near Tequila. Even the heritage site covers several different towns west of Guadalajara.

Between Tequila and Guadalajara is a UNESCO Biosphere, La Primavera or ‘springtime’, which includes a pine-oak forest, springs, orchids, birds and more, and it’s a popular recreation area. Tequila is my last stop in Mexico for a while—quite an enjoyable one—, so now Mondays switch back to US park units, affiliates, trails and heritage areas. Thanks for reading!

Originally designed to be a hospital, like Les Invalides in Paris, and named after the bishop, today the World Heritage Site in the historic heart of Guadalajara is a museum, with modern art outside and exceptional murals by Orozco inside. The central masterpiece on the ceiling of the rotunda is ‘The Man of Fire’, a modern version of the myth of Prometheus (in photo on right). I had seen Orozco’s earlier version in the Pomona dining hall in California, considered “the greatest painting in America” by Jackson Pollack. Orozco lost his left hand making fireworks at 21, and he was fascinated by the story of a man who risked his life and suffered to expand human knowledge and civilization, only to be punished by the Gods. He felt the myth was an allegory for artists, explorers and reformers who were punished by conservatives for their efforts to bring enlightened change to the people. Every alcove and wall tells a story of both progress and betrayal, of historic accomplishments and dark consequences.

Prometheus stole fire from the Gods, but today we struggle with the consequences of burning carbon. Fossil fuels helped us achieve great things, but there are always consequences. Struck by the inescapable conclusions of the art here, we see that conflict over ‘progress’ often results in suffering, especially among the poor. Murals require us to step back, to try to see the bigger picture. We can build hospitals, and we can also destroy whole cultures. We can choose sustainable fuels, or we can let powerful men perpetuate destructive fuels. We may believe ourselves invincible and deserving of the powers of the Gods, but our actions come with destructive consequences that we must try to see, understand and prevent. We must give up fossil fuels, or our world will burn.

I arrived at this World Heritage Site on Sunday late morning, and with a minor miracle I found parking one block from the cathedral above. When I stepped inside a beautiful mezzo-soprano voice echoed through the high ceilings and alcoves. What a spectacular and moving service!

The city and state are named after José Morelos, born a block behind the cathedral (now a museum), a priest in the cathedral, who answered the cry for independence and supported multi-racial equality. Morelos also demonstrated remarkable skill as a military strategist, and after Hidalgo was executed in 1811, Morelos became the leader of Mexican Independence. After dozens of victories that roused the insurgents, Morelos was eventually captured in Puebla, tried by the Inquisition, defrocked and executed near the end of 1815. He is remembered as one of Mexico’s founding fathers.

Full disclosure: the three houses here were being renovated the week I was in Mexico City, and it is only on the tentative UNESCO World Heritage Site list. Architect & artist Juan O’Gorman had the complex built for the famous couple while they were touring in the US in 1931-32, and their patrons the Kaufmanns, of Fallingwater, visited the couple here in the upscale San Ángel neighborhood in 1938. The big house and studio in the front was Diego’s, the blue one was Frida’s, and O’Gorman lived in the third house in back. There’s a bridge between Diego & Frida’s homes. This arrangement worked for about 5 years, but then they divorced.

To be clear, Frida’s blue house above is not La Casa Azul, The Blue House, where Frida was born and died. That more famous one is in the Coyoacán neighborhood less than an hour’s walk away. Frida hosted Leon Trotsky there, after helping him get asylum, although he was ultimately assassinated in his home nearby (now a museum). Diego & Frida remarried and lived in her original home until her death, keeping the complex above as Diego’s studio. Diego Rivera donated Frida’s Casa Azul as a museum, and it’s one of the most visited sites in the city. Tickets to her home and museum are essential to buy online well in advance, as they recently stopped offering in person ticket sales.