Gros Morne, a world heritage site in Newfoundland, has three must sees: Gros Morne Mountain, the Tablelands, and Western Brook Pond. The first can be seen easily from many viewpoints, and the approach trail is reasonably flat. The whole park is famous for its geology, with rocky coves, pond marked plateaus, deep fjords, dark, magnesium rich cliffs and the lonely mountain of Gros Morne itself, with pinkish quartzite on top. The views from the top are supposedly stunning, but it’s an all day steep hike.

The second must see above is unique and has an easy guided hike. The Tablelands is one of maybe three places in the world where you can walk on the earth’s mantle. Left over from a temporary overlap and receding of the North American and Asian tectonic plates, this mountain of mantle cooled, dried and had its crust removed by glaciers and erosion. The Table Mountains are studied by geologists—including those who developed the theory of plate tectonics—, and it is easy to see soapstone, serpentine, and other interesting rocks here. But most of the rock above is peridotite, an iron rich igneous rock from the mantle.

I took the ‘easy’ Tablelands hike with a guide who explained about the tough creatures who live up here, including the local humans. The forecast was clear all morning, so naturally it hailed and rained for much of the hike. Still, the clouds occasionally parted and revealed some of the muted yet dramatic scenery.

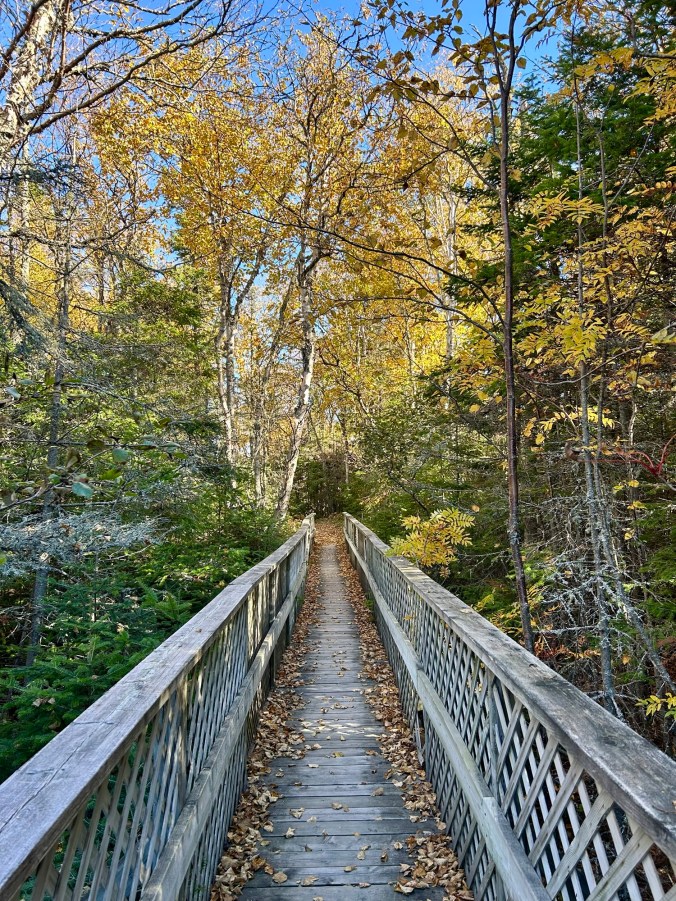

And the third must see also has an easy hike, but then you need to take a boat to see the rest. Western Brook Pond is actually a deep lake in the middle of a landlocked fjord, with high thin waterfalls cascading down massive cliffs. Glaciers carved many fjords, arms and valleys in the park, and this spot offers a great view of the ancient Appalachian landscape. On a good day, it is spectacular, but the weather doesn’t always cooperate.

I would recommend scheduling more time than usual for Newfoundland, as the pace is slow, weather is changeable, and delays are common. I will have to return to see a couple places that I missed due to a ferry cancelation. On the other hand, I’ve been forced to slow down my typical hectic schedule, which is good.