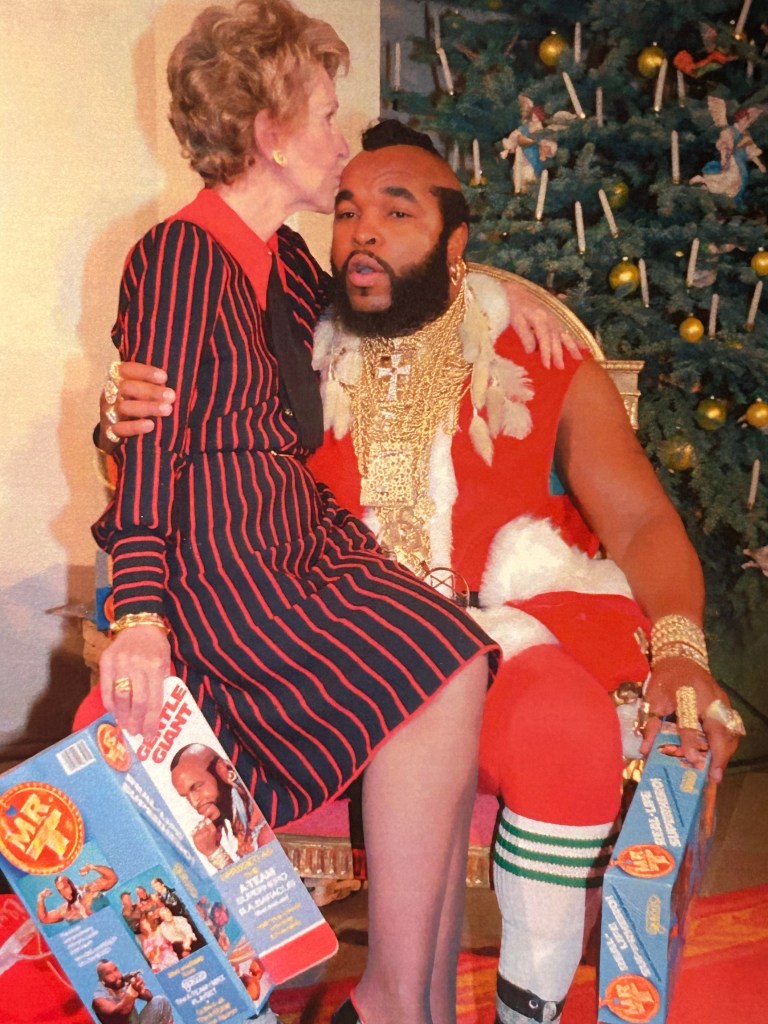

Hope you had a Merry Christmas! Enjoy this next installment of how to fix our thinking problem by clarifying our four distinct ways of thinking. Lots of us get sentimental around the holidays, so there’s no better time to delve into instinctual thinking.

Observe and mimic

As animals, we follow our instincts, observe and mimic. We underestimate how influenced we are by what we observe. Our species—Homo sapiens—evolved larger brains and more sophisticated vocal anatomy than our predecessors, enabling us to communicate complex ideas through words. But our predecessors—Homo erectus—accomplished much despite their lack of language. They drew art and symbols, crafted tools and weapons, they mastered fire and they organized into communities. Our species began with knowledge of all of these elements of human society, before we invented the words and grammar to describe them. Wordlessly, our ancestors conveyed how to be successful humans, including cooking, hunting, raising families and living in tribes, through observation and mimicry, over thousands of generations.

We still learn this way. Our DNA contains the basic human design, but our species has always augmented that recipe with a sophisticated set of imitated human behaviors we learn from observation: how to use tools, communicate, and behave together. Babies learn very quickly by observing their families, before they learn any words. Parents pantomime behavior they expect their babies to mimic, such as opening our mouths while spoon-feeding. And throughout our lives now, we learn more behaviors while watching videos than when reading, because unconscious observation is the primary way our species has always learned.

Instinctive versus instinctual

Instinctive implies inherited behaviors, like our instincts to survive or reproduce. All humans are the same species, so we share the same physiology and basic emotions. Anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness and surprise are all easily recognizable human emotions, because our faces express them with eyebrows or lips moving up or down, jaw or cheeks flexing or relaxing, and eyes widening or tightening. These emotions are genetic, universal, unconscious, and evolved over thousands of generations, because communicating our emotions visually helps us thrive.

Instinctual—as I define it—includes both the traits we are born with and adds what we unconsciously learn as humans. While some facial expressions are genetic, others are learned through observation and mimicry. Often our genetic traits are indistinguishable from our unconsciously learned behaviors, so it’s useful to group them both together as instinctual.

Instinctual motives

Think about what motivates you. Are you devoted to your family, your significant other, your friends or your pets? Are you working to make your life more comfortable, to enjoy good food, and to have fun? Do you make an effort to dress well for an event, for colleagues or for any gathering? Do you wish you were more appreciated, recognized or admired? Is being in a relationship where you can share your feelings and spend time together intimately important to you? Do you enjoy supporting your local sports team and cheer when they win? Afraid of dying?

These are all normal, powerful instinctual motives. In many cases, the thinking is simply, “I want it, it feels good, so that’s what I’m doing.” It does not matter whether it is conscious or unconscious, whether it reflects a physiological need or an evolved group behavior, whether you are intelligent or well-educated, or whether you are following the crowd or leading it. If the root cause of your motivation is physiological or determined by your social needs, then what drives you to think and act the way you do is instinctual.

Instinctual behavior

Most people primarily behave instinctually, without really thinking. Does such categorization offend you? Do you want to object, argue or fight about it? Do you suspect that you are being judged or having your status questioned? Are you preparing to say that all humans are this way and nobody is any better? Then thank you for confirming. You instinctively feel threatened by a mere description and want to fight about it. Rather than dispute what drives us, we should welcome our instinctual motives and behavior as what makes us human. There’s nothing inherently wrong with satisfying our basic needs, protecting our child, flirting, or needing group approval. Our species would not survive without those instincts.

Instinctual motivations are what cause most of us to get out of bed, to groom, eat, exercise, work, rest, have fun and spend time with each other. Instinctual motives drive most actions, longterm habits, rituals, and even desire for change. Without that fire in our gut, most of us would not take that first step to accomplish anything. Instinctual feelings can also depress us, make us give up too soon or paralyze us with fear or doubt. Whenever we interact with others, we take in non-verbal cues and react instinctually, straightening our backs, baring our teeth in a smile, maintaining eye contact while extending an open hand. We instantly adopt a posture of helpfulness, defensiveness, confidence, aggression, flirtation or curiosity.

Our instinctual desires choose how we entertain ourselves: action, comedy, crime, horror, drama, porn, romance or thriller. We often behave this way at work, when we decide where to sit during the meeting, who to team up with and whether to seek out or avoid confrontation. Our desire for recognition, to be attractive and to dominate others are common human traits, and they drive our behavior more than other ways, whether we are conscious of them or not.

Instinctual thinking

The different ways of thinking are primarily distinguished by motive. Instinctual thinking is driven by instinctual motives, consciously or not. We may not be aware of our unconscious motives, but we still feel them. They drive us to act instinctually, including displaying complex social behaviors, towards an instinctual goal, regardless of how much we initially realize what’s really driving us. Later, we often become aware of our instinctual motives simply by observing our behavior. Awareness helps us improve our instinctual behavior, through conscious instinctual thinking.

Those who have a finely tuned sense of instinctual motivations or who send all the right signals have social advantages over those who miss social cues or give off weird signals. Unconsciously we judge each other by tone of voice, stance, handshake and a look in the eye. If they appear confident, then we believe them. Do they remind us of others who were good or bad to us? Who appear to be winners and losers? Our internal instinctual drives often determines who we fear, flatter, imitate, join or avoid. Once aware of the instinctual games we all play, we can control our own instincts, influence the behavior of others and even influence group dynamics on a large scale. In this way, the dominant rule, and the subservient follow.

Instinctually-oriented folks feel in their guts that this is how the world works.