Rational thinking is work, which benefits from training and accumulated skill, but requires mental effort and discipline. There are specific tools and techniques designed for analyzing different subjects, and using appropriate techniques for your rational analysis is integral to achieve your end goal or solve your question. Education helps, but having knowledge or training is no substitute for doing the work of thinking logically and for applying logic consistently throughout your life. Occasionally over-trained people can be thoughtless and just go through the motions, rather than observe carefully and think through each important step. Over-thinking happens when you hesitate to follow through to your logical conclusion, especially when you are irrationally concerned with whether your answer is acceptable. Above all, rational thinking must be honest and accurate, with complete integrity, from beginning to end.

For many, simply making an effort to think rationally is an improvement over common instinctual thinking. Try to be dispassionate, ask yourself questions, observe the facts neutrally, see if you can get more information, use logic to figure out what’s going on, consider the probable outcomes, be skeptical and find ways to test to see if you are correct. Congratulations, Madame Curie, you are following the scientific method.

Many self-professed rational thinkers divide humanity by intelligence quotient. If someone is not rational, logically they must be irrational. If you’re rational, you’re smart. If you’re not rational, you must be stupid. This simplistic view of thinking is ignorant. Folks who cherish their loved ones, have strong bonds of friendship, work hard, and are well-liked in their communities, do not appreciate being called stupid. So, one step to improve rational thinking is to recognize that IQ doesn’t measure all ways of thinking and to realize that other ways of thinking are both valid and often more appropriate in different situations.

Even predominantly rational thinkers must be familiar with instinctual thinkers. While you were achieving in school academically, the instinct-driven majority likely did not make school easy for you socially. Were you “a nerd”? Did people criticize your hairstyle or fashion choices? As an adult, have you found yourself overseen by someone more politically adept than you? Meritocracy often eludes rational thinkers. Turns out that the attention to social cues, team dynamics and competition for status, which you might ignore, matter more than merely knowing the answer.

Also, it is not rational to feel smug about your IQ. Your concern with your status betrays your instinctual thinking. Perhaps calling others stupid is a childhood defense mechanism to the trauma of being bullied or ostracized as a nerd? Truly rational thinking is not driven by human emotions or primal urges. When a seemingly rational argument turns out to be driven by a deep-seated instinct, it may be false, deceptive and biased, and since it is not the product of rational thinking, then it is irrational (e.g. most political arguments).

Another error is to conflate knowledge with rational thinking. Memory is over-prized, and speed of recall is confused with intelligence. Nonsense. A good rule of thumb is that if you can do it in your sleep, it’s probably instinctual thinking, not methodical rational thought. I recall people, places, conversations and scenes vividly in my dreams, while being blissfully unconscious, and I might even talk in my sleep. Clearly, remembering or reciting facts is not proof of rational thinking, let alone consciousness. No, only when you have the intelligence to understand which facts are most relevant and actionable before offering a solution, have you demonstrated rational thought. I once aced a test without reading the chapter by glancing over my classmate’s notes two minutes before the test, even though she only got a B-. I understood the concepts better than her, knew what was important and accurately predicted the questions, even though she had memorized all the facts.

When the origin of your thinking begins in one way, then the results will likely reflect that way. You may believe you are thinking rationally, but if you began with a different way of thinking, your final report will probably reflect it. Even if you assert your rationality mid-process, you may have ignored crucial data or have already structured your approach to achieve a specific result. People walking by your desk watching you work on your spreadsheet believe you are thinking rationally. Your boss skimming your report believes it to be the product of rational thinking. But, if your motive is not rational, then your analysis will lack the integrity of accurate rational thinking.

Perhaps you are at work looking at the numbers on your screen as you usually do on Monday morning. You are not responsible for the data, there’s no risk to you, and if you were not being paid to look, you would not check them. You are detached and dispassionate. You do not care. But the numbers show a different pattern than usual. The change raises several logical questions, so you look into it. That is a rational way of starting to think.

Suppose instead that there’s a reason you decided to look into the numbers. Maybe the numbers are personal to you. Maybe a positive report will help a cause you support, or maybe the results will prove a pet theory you have that you feel deserves recognition. Perhaps the results show that your friend is not on track to meet quota, or maybe you are not. The boss is just looking for an excuse to embarrass you at the staff meeting this afternoon. In this situation, your instinct to protect your self esteem is likely driving your thinking, so you do not begin thinking rationally.

The method of thinking you use does not matter, if your thinking begins on the wrong track. You may employ advanced analytics, but if your driving goal is to support your cause, your report will not be entirely fair, which is not rational. You may write a book with charts, graphs and long-winded, elaborately structured arguments, but if it is done to support a figment of your imagination, then it is not rational. You may decide to postpone your analysis until after your boss goes on vacation tomorrow. You may believe that is a rational tactic to protect your personal interests, but it is instinct-driven thinking.

The most important step towards better rational thinking is to begin rationally. Are you too invested in the cause to be certain that your analysis will be impartial? Do you have a pre-conceived notion of what the numbers will show? Can you get control of your personal feelings and conduct the analysis rationally? You may need to ask a neutral person to do the analysis. You may need to find a rational way to eliminate your bias. Or you may need to grab a hold of yourself, be as professional as possible, and let the numbers speak for themselves.

That may be obvious to you at work, but can you be equally dispassionate when making rational decisions about yourself and your loved ones? I’m not asking you to suppress your natural instincts. Be aware of them, and control them. Then apply rational thinking to your problem honestly, without instinct biasing your beginning, with appropriate logical methods, to arrive at a sound conclusion with integrity. Then you can decide to do what you want, but at least you can be confident that your thinking is correct.

“Five percent of the people think;

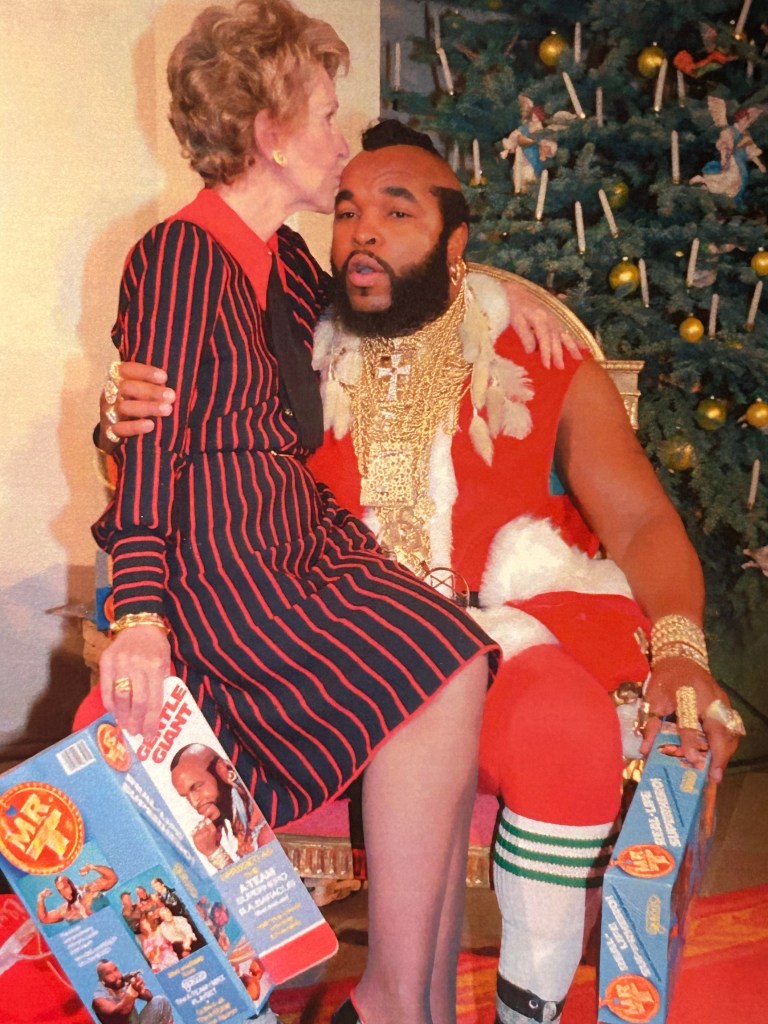

— Thomas A. Edison, study pictured at top

ten percent of the people think they think;

and the other eighty-five percent would rather die than think.“