Often, there’s a local reluctance to allow government outsiders to tell ‘our’ history. Communities will occasionally refuse to cooperate or turn over any control over their sites to the National Park Service. Reagan’s boyhood home famously stays independent, concerned that his legacy might be tarnished. Sometimes politicians get involved directly in changing the way history is told, and even bend the narrative away from self-evident facts, such as at Andrew Johnson’s site.

Debates often become heated with charges that one side is “revising history” to fit preconceived views. But honest historians do not rewrite history to suit their tastes. A good historian should try to revise their understanding of history, always to make it more accurate. In the UK, “revising” means “studying for exams”, meaning reviewing the material to understand it better. Sometimes a new fact comes along, such as a DNA test proving who is related to Thomas Jefferson. Views and interests change too, which also require us to revise our understanding of history, as we have new questions to answer. Future history books must be updated to include the most accurate information and to address the needs of future generations.

Bad historians ignore new facts, preferring the old version they learned, even if false. Some even intentionally mislead children to try to hide shameful episodes, claiming to protect them from the truth. Some dishonestly smear historical figures or downplay historic events in order to promote a world view based on propaganda, such as what happened with General Grant. Lying to kids or trying to brainwash the public to further a dishonest agenda is never acceptable.

But the park service has experience and expertise to help sites reach more people accurately and effectively. They hire researchers to find more information to expand everyone’s knowledge. They conduct renovations carefully to restore sites to how they appeared at specific times. They know how to create films, displays and foreign language brochures. Sometimes the park service gets it wrong, prompting debate, review and new efforts. Sometimes the site is best managed by a specialized local group, often in partnership with the park service, such as the Tenement Museum in NYC. Still, the park service’s job is to preserve, inspire, educate and make sites more fun for all. So typically, it’s at least worth letting them help.

I have a good education, do extra research on each site and form my own views, but I also try to understand, verify facts and frequently ask questions. Almost always, the park rangers can quickly disabuse me of erroneous views, since they are experts. Occasionally, I meet the odd ranger with views in contradiction to the facts or find errors on display, and I bring those to the attention of other park service employees. Getting the stories right can be difficult, but almost always the park rangers are determined to do their best to tell the story correctly, effectively and well. That’s what they do.

I mention this now, after visiting the Gulf Islands site. In both Mississippi and Florida, the park service does a good job in accurately telling the history of the gulf coast, including the dark history of the Civil War. Unfortunately, the US military turned over the most important historical sites, Forts Gaines and Morgan, over to the state of Alabama, where I’ve observed troubling patterns. I believe the national park service would do a much better job telling the history.

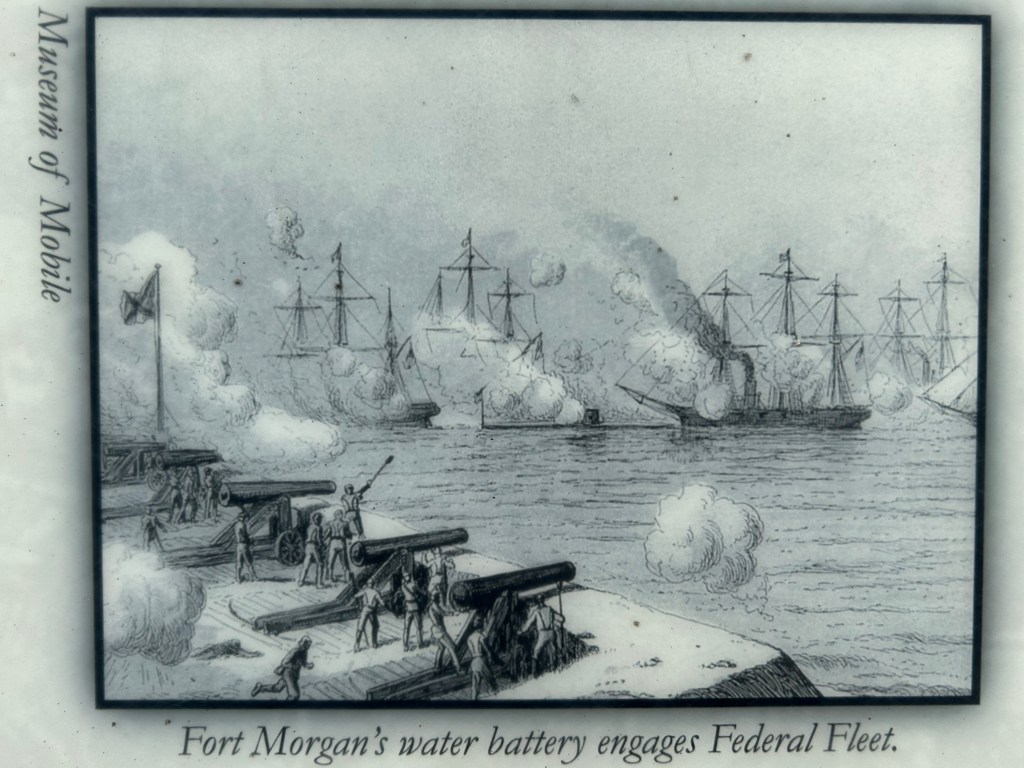

Visitors to Fort Morgan might not learn which side won the Battle of Mobile Bay or why that matters. The information may be there, but it is not presented effectively. Here are my recent notes.

- Website focuses on the history of old fort Bowyer more than the Civil War era Fort Morgan.

- Park brochure timeline covers fort’s history but buries highlights in obscure details.

- The Battle of Mobile Bay battery site and plaques are not shown on the map.

- Civil War panel neglects critical Union victories at the end, such as Richmond, Petersburg and the surrender at Appomattox.

- Flag pavilion plaques show the US flag as only operational in 1813, ignoring the period from 1864 to the present.

- Posters in gift shop celebrate the sinking of the Union ship Tecumseh and the early success of the CSS Tennessee.

- Bookstore focuses on Confederate defense of Mobile 50 miles away, rather than on the pivotal Union naval victory of Mobile Bay 50 yards away.

There are only two ways to reach the Battle of Mobile Bay battery site.

- 1) go straight through to the far side of the fort, enter a series of tunnels (use your phone for light) on the right, wander through a maze of passageways, pass through several huge empty rooms, find a small doorway around a corner leading outside, return on the grass between the inner and outer walls, cross the moat, climb a ramp (no handholds) to the top of the outer wall, climb steps through some fortifications, climb some more steps, and go around the outside of the fence that appears to block your path. Or….

- 2) go behind the restrooms on the far side of the parking lot, climb up through a different battery of fortifications, walk along to the far left, find a narrow stairway up a hill, climb it even though it appears to be blocked at the top, wander along the top of the outer wall to the outer edge of the fence mentioned in step 1, circumvent it and climb up to the top above Battery Thomas.

In neither case are there any signs, arrows, map references, guideposts or signals to find the spot, and it’s best to wear sturdy non-slip shoes. Finding the well-written and illustrated displays (e.g. photo above) was a nice surprise, as I only climbed up there because I got lost exploring and wanted to get a look at the ship channel. Frankly, hiding the panels appears to be an intentional effort to obscure or erase the true and important history that led to the end of the Confederacy and slavery.

If the park service managed the site, I’m sure they would tell the story of one of our country’s greatest naval victories accurately and effectively, preserving that important history, inspiring, educating and delighting future generations. Especially today, on the first day of Black History Month, it’s critical to get history right. That’s why we need the NPS to help us with our history.