Instinctual thinking is the first of four ways of thinking that we must improve to fix our problem with thinking. The most common way of behaving is instinctually, meaning driven by physiological needs, instincts, and evolved social needs. While often unspoken, instinctual motives are powerful and potentially dangerous. Understanding our instinctual motives and behaviors is the most important and useful way of thinking.

The ancient Greeks inscribed ‘know thyself’ on Apollo’s temple at Delphi, because when we know ourselves well, we can also better understand others and we can think about how to be better humans. Our society is largely determined by how our instinctual behaviors operate in concert with other people’s instinctual desires, expectations and behaviors. Once we realize the instinctual motives at play, we can consciously improve expected behaviors, both our own and others. Those who unwarily ignore their own and others’ instinctual motives are more likely to make social faux pas or to leave themselves open to instinctual manipulation.

Awareness

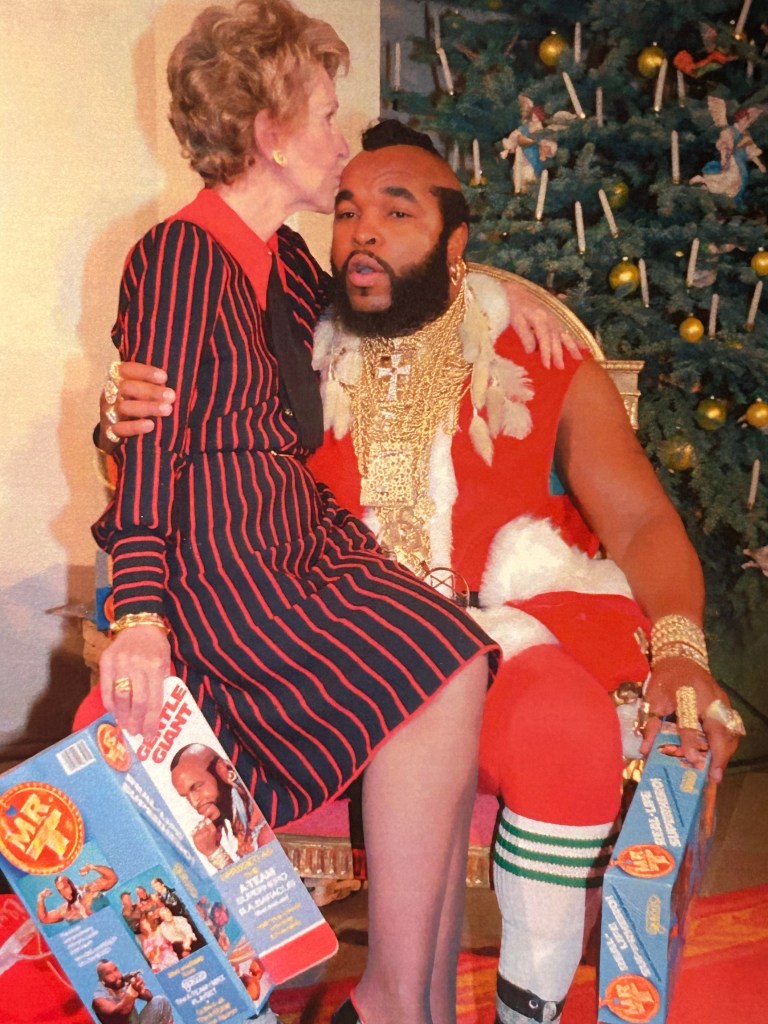

Wondering why we behaved a particular way—or even denying having an instinctual reaction—is how we become self-aware and begin conscious instinctual thinking. Awareness of our instinctual motives and behaviors enables us to control our reactions. Upon seeing a skunk, a sudden reaction might be unwise. But if you realize it is a baby, without fully developed scent glands, you can override your instinctive reaction and take a close up photo below.

Try to be conscious of your instincts, identify them and understand whether they are inherited or reflect your upbringing. Why are you drawn to certain relationships or work hard to impress others? What causes your anger or embarrassment, joy or sadness? Is the root instinct hard-wired into your DNA or is it merely conventional? Did the instinct evolve from 200,000 years of fighting animals and each other, or did it evolve over the past 10,000 years since humans began living behind the walls at Jericho? Is the instinct useful or should it be obsolete? Is it a reaction from childhood that you should finally deal with as an adult? Is it simply based on some cliché you have frequently observed on screen? Without effort, you might confuse a valuable instinct with a false impression formed unconsciously; the former may keep you alive, but the second may be a costly mistake.

Conscious instinctual thinking helps us understand ourselves, predict our own behaviors, and even through willpower to harness our instinctual motives to improve our behavior. The effort is worthwhile. After we experience trauma, instinctual thinking is often required to process what we unconsciously internalized, so we can recover and progress. At home, you need to be aware of your own moods and those of others. At work, you may choose to emphasize flattering words or numbers, acting on your instinct to ingratiate yourself; awareness of your instinctual motive may allow you to behave more professionally. Be honest and aware of when your instincts drive your thinking. Be suspicious of your own motivations as well as others’; you have the instinct of suspicion, so use it.

Self control

Normally, we follow our instincts. But we also try to control them. We may overcome our fear, enhance our bravery, delay gratification, refrain from violence, or harness our adrenaline. Different situations call for different behaviors, and we adopt different postures with different people. We may smile, laugh, make or avoid eye-contact, grimace, show our unhappiness, or stand up straight and get in someone’s face to intimidate them. Being aware of our instinctual displays makes them more intentional and effective.

If we don’t know why we behave certain ways, then we are at a loss to control them. With experience, we manage our emotions, temper and guide them appropriately. Understanding a trigger may help you process your emotions more effectively, so you can move from shock, past anger, through sadness to be calm. Humans evolved both display and interpretation of emotions; use yours. When observing others, we sense their emotions and choose our response, reflecting both our own emotional experiences and being in similar situations with similar people. Be empathetic, express your feelings nonverbally too, but use your emotional intelligence to respond in the most helpful way, cool or warm, dismissive or supportive, with humor or affection. Our most important acts may need no words.

Some try to deny and suppress their instincts, but instincts need to be acknowledged, understood and dealt with productively. Pretending to be one person, while your instincts want you to be a different person, is a recipe for trouble, potentially shattering. Self-help books and seeking help from others can be worthwhile, but since only you know your true instincts, you need to understand them. Be aware of the instincts at play, and address them appropriately: accept, adapt, choose, discuss, dismiss, forgive, laugh, learn, redirect…. Dealing with our instincts consciously gives us more advanced options to decide what to do: creative, moral and rational. Don’t use your advanced thinking to crush your instincts, but find a way to realign your instincts to drive your life in the best direction. You always have more options than you realize at first.

Pulling the strings

We must not underestimate the power of unconscious learning to influence us. Within us we carry both deeply engrained complex human behaviors that predate our species and newly formed impressions from social media feeds. Changing the first often seems unthinkable, even when ancient tribal behaviors are now obsolete. And changing the second happens constantly, as each new generation now grows up with significantly different technology. A multigenerational family will have distinctly different unconscious behaviors and expectations formed by very different childhood experiences. Many infants today have no opportunity to see fire at home, let alone have deeply impressed memories of fireside chats huddled around a hearth.

Everything that we observe can seep into our unconscious to emerge in our dreams or our behavior, instinctually. Our modern, social media engaged lives are full of conscious campaigns designed to control our instinctual behavior. Whole industries are geared to manipulating our behavior by creating scenes for us to observe. The characters on screen using a product appear happy, strong, attractive, healthy and confident, so, unconsciously, we feel inclined to purchase the product. While you may know that the ad is selling something, you probably are unaware of the PhD level psychological marketing behind the advertising campaign designed to influence your unconscious towards a targeted behavior. Conscious instinctual thinking is also the first defense against manipulation by others.

When we unconsciously follow our instincts, perceptive people may use our instincts to manipulate us, if they are more conscious of what drives us than we are. Once we become aware of what drives us and understand why, then we gain the ability to defend ourselves against those who would control our behavior by pushing our buttons or pulling our strings intentionally. Whole industries exist to take advantage of your emotions and instincts to drive your behavior for their profit. Awareness gives us control, and understanding our instincts lets us decide whether to follow along or refuse to be treated like a puppet.

The goal of instinctual thinking

So the goal of instinctual thinking is to improve our human condition and to avoid misery. Our instincts did not evolve to ruin our lives, bankrupt us or make us miserable. That is lack of instinctual thinking. Instinctual thinking evolved to help us sense, feel, learn and harness our instincts for our benefit. We think this way to avoid pain or embarrassment, to experience pleasure, and feel comfortable. We want to be filled with joy, feel pride, love and be accepted by others. We think this way to gain status, protect our reputation, gain followers, and defeat rivals. If we misread a social cue and people laugh at us, we try not to make that mistake again. If we do not pick up on someone’s emotional state and unintentionally provoke an angry outburst, then we need to improve our instinctual thinking both for our own benefit and for the benefit of those we love. By being more conscious about our instinctual thinking, we can use it more effectively.

We ignore our instincts at our peril, but when an instinct is no longer helping us, we can learn to disregard it. Once we realize that an instinctual reaction is due to a painful childhood experience, we can forgive the long-forgotten act and move forward. Once we become conscious of our instinctual goal, we can take conscious steps to achieve it. Honestly facing a destructive instinct, gives us the chance to redirect it creatively. Understanding that our sweaty palms evolved to grip a weapon before combat, helps us reinterpret stressful social situations as not actually requiring combat. Discerning whether our instincts are driving us where we want to go or whether we are being manipulated by someone, gives us more control over our lives. Instinctual thinking is used to make the most of our instincts, and not just follow them blindly.