November is Native American Heritage Month, and next week is the 403rd anniversary of the first Thanksgiving feast of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, when, as earlier in Jamestown, Native Americans helped starving English colonists. Contrary to the gauzy fabricated myth that natives peacefully welcomed Christian settlers and happily ceded their lands, tribes were decimated by disease and were massacred in both the Pequot War and King Philip’s War. Thanksgiving was first declared a national holiday by Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, at a time when the US government was also at war with the Apache, Commanche, Navajo, Sioux, Ute and Yavapai, among other tribes. In the interests of truth, this post will focus on the NPS sites of the US War on Native America from the Revolution to 1924.

Our Democracy owes a debt to the Iroquois Confederacy formed 882 years ago, the oldest living participatory democracy. Ben Franklin was a student of Hiawatha’s Law of Peace which united 5 (later 6) tribes on issues affecting them all, while allowing them each to manage their own tribal issues separately. Thus, 13 colonies united to gain independence, becoming the United States. In 1794, George Washington signed the Treaty of Canandaigua recognizing our allies the Oneida, who fought with the Patriots at Fort Stanwix and Saratoga. The other tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, many having fought for the British, had lost most of their lands in the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

For Native Americans, war with the US continued non-stop, moving northwest near Fallen Timbers and southeast near Chickamauga and Chattanooga. Despite winning the most successful native battle against the US army at the Wabash River, the pattern of natives losing their land regardless of whether they fought or which side they joined continued. The River Raisin set the stage for the War of 1812 and made the issue of claiming native land a mainstay of presidential campaigns. General Jackson leveraged his victory at Horseshoe Bend to become a popular national figure, and as President, he defied the Supreme Court to remove many tribes from the southeast to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears.

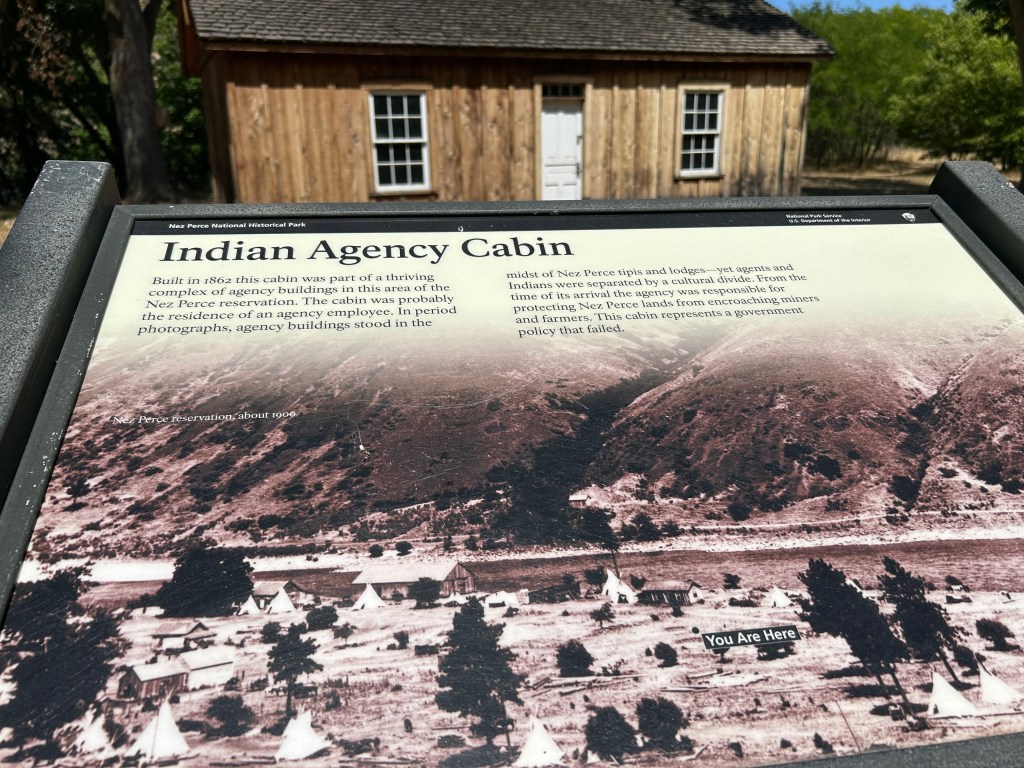

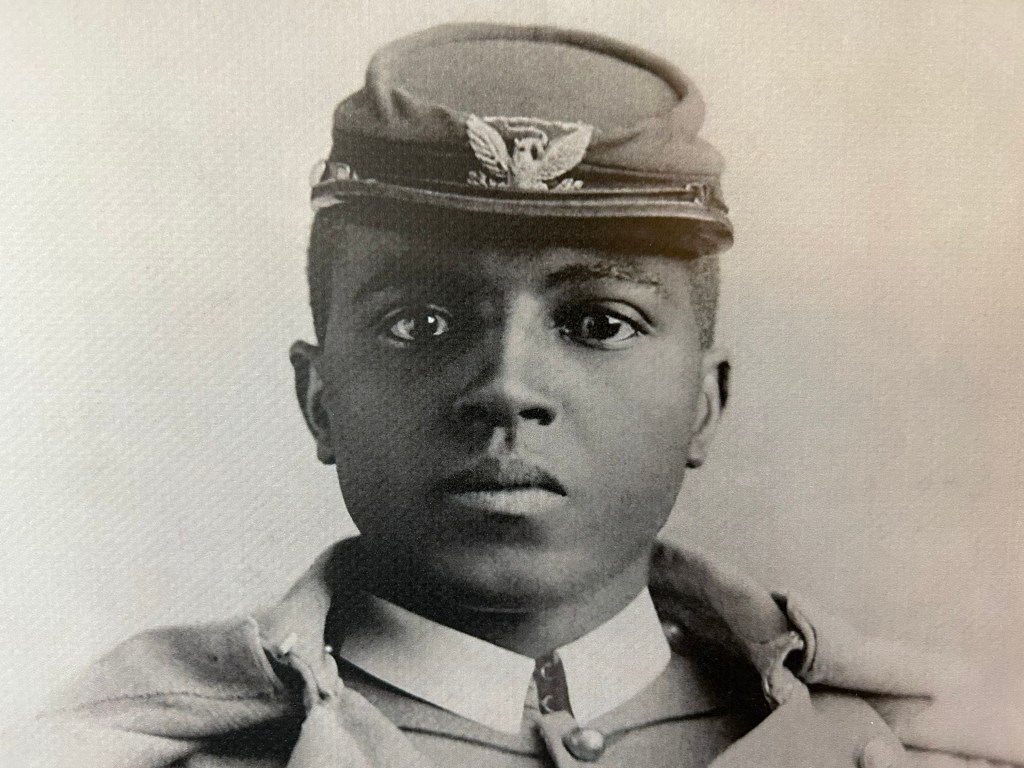

As the country expanded out west, following the scouting trip of Lewis & Clark, the US military used a network of forts in their continuing war against natives along the Old Spanish Trails west of the Mississippi: Arkansas Post, Fort Smith, Fort Scott, Fort Larned, Fort Laramie, Fort Davis, Fort Union, and Fort Bowie. Each was involved in supporting hundreds of one-sided battles against Native Americans, often involving Buffalo Soldiers in remote places like Chiricahua. While there were a few forts, like Fort Vancouver and Fort Union Trading Post, that were peaceful, there were also other forts like Bent’s Old Fort, Hubbell Trading Post and at Pipe Spring that were involved in the destruction of native tribes, often by destroying their food supplies. And after being cleared of natives, the Homestead Act gave their land to settlers for free.

And there were massacres. Not the rare US military defeat like at Little Bighorn. Not the few sensationalized or many fictional stories of natives killing relatively small numbers of white settlers, like at Whitman Mission. But the illegal massacres of hundreds of peaceful villagers by US Army regulars and volunteers at Big Hole above, Sand Creek, and Washita Battlefield, among many others not yet memorialized by the NPS. Even our national monument to great presidents at Mount Rushmore is not far from the massacre site at Wounded Knee.

The US War on Native America is not usually considered as one continuous war, but rather as over 60 different military conflicts, often overlapping, between 1775 and 1924, when the last Apache raid was conducted in the US and when Native Americans finally got the right to vote 100 years ago. However, the US was at war with various Native American tribes in the years from 1775 to 1795, from 1811 to 1815, 1817-1818, in 1823, 1827, 1832 and from 1835 to 1924, or for 121 years of active fighting, plus 29 years of intervening “peaceful” forced removal by the US and state governments, even of tribes which had assimilated. Taken as a whole—including forcing dishonest treaties, abrogating treaties, suspending promised annuities, terminating trading relations, cheating tribes in unfair land deals, preventing private land deals with natives, relocating natives when gold was discovered on their land, revoking Indian land titles, seizing tribal land, annulling tribal constitutions, challenging their rights in court, dismissing their victories in court, dividing tribes, destroying crops, killing livestock, slaughtering bison, subsidizing exodus, rounding up tribal members into camps, locking them in forts, and forced marching them 1,000 miles over 5 months under US military guard—, the US government policy of removing Native Americans by force was a single policy, confirmed by multiple US presidents, passed into laws by Congress, and executed by the US military with deadly force against one group, known collectively as “Indians”—as in the “Indian Removal Act” of 1830—. So, rather than being dismissed as dozens of piecemeal conflicts, the US military actions against all the tribes should be considered as a single 150 year long, genocidal war.

It is horrifying to me that we do not recognize our nation’s longest war, even in the 100th anniversary since its end. We have largely forgotten the roughly 100 tribes that are now extinct, as well as the Pontiac War which used smallpox blankets, the Potawatomi Trail of Death, the Long Walk of the Navajo, the Yavapai Exodus, and others. And we in the United States—founded under a Native American democratic organizing principle and living on native land—do not admit that the long, costly war, devastating relocations and cultural destruction, was repeatedly approved by racist American voters.

“The wounded, the sick, newborn babies, and the old men on the point of death…

Alexis de Tocqueville, on witnessing the Trail of Tears in Memphis

I saw them embark to cross the great river and the sight will never fade from my memory.

Neither sob nor complaint rose from that silent assembly.

Their afflictions were of long standing, and they felt them to be irremediable.”