The southeast region has more park units (70) than any other region, and I have visited all the units—*except 6 in US Caribbean territories—including all the affiliates, heritage areas and trails in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee. Given the large number of states and parks involved, the summary below is organized by theme.

Natural Areas

All of the National Parks in the southeast preserve natural areas, including the reef area of the Florida Keys from Biscayne to the Dry Tortugas, the lowlands of Congaree and the Everglades, the Great Smoky Mountains, and even underground at Mammoth Cave. Other park units, Canaveral, Cape Hatteras, Cape Lookout, Cumberland Island and the Gulf Islands, protect barrier islands. Big Cypress, Big South Fork, Chattahoochee River, Little River Canyon and Obed River all protect diverse riparian areas.

Pre Civil War

Ocmulgee Mounds, Russell Cave and Timucuan stretch back before history, but Horseshoe Bend covers a tragic event in Native American history. Several sites cover early colonial history, including Castillo de San Marcos, De Soto, and Forts Caroline, Frederica, Matanzas and Raleigh. Cowpens, Guilford Courthouse, Kings Mountain, Moores Creek and Ninety-Six cover the Revolution. Blue Ridge, Cumberland Gap, Lincoln Birthplace, Natchez Historic–Parkway–Trace, and Pinckney, trace the path of history in the southeast, culminating in the war to abolish slavery.

Civil War and beyond

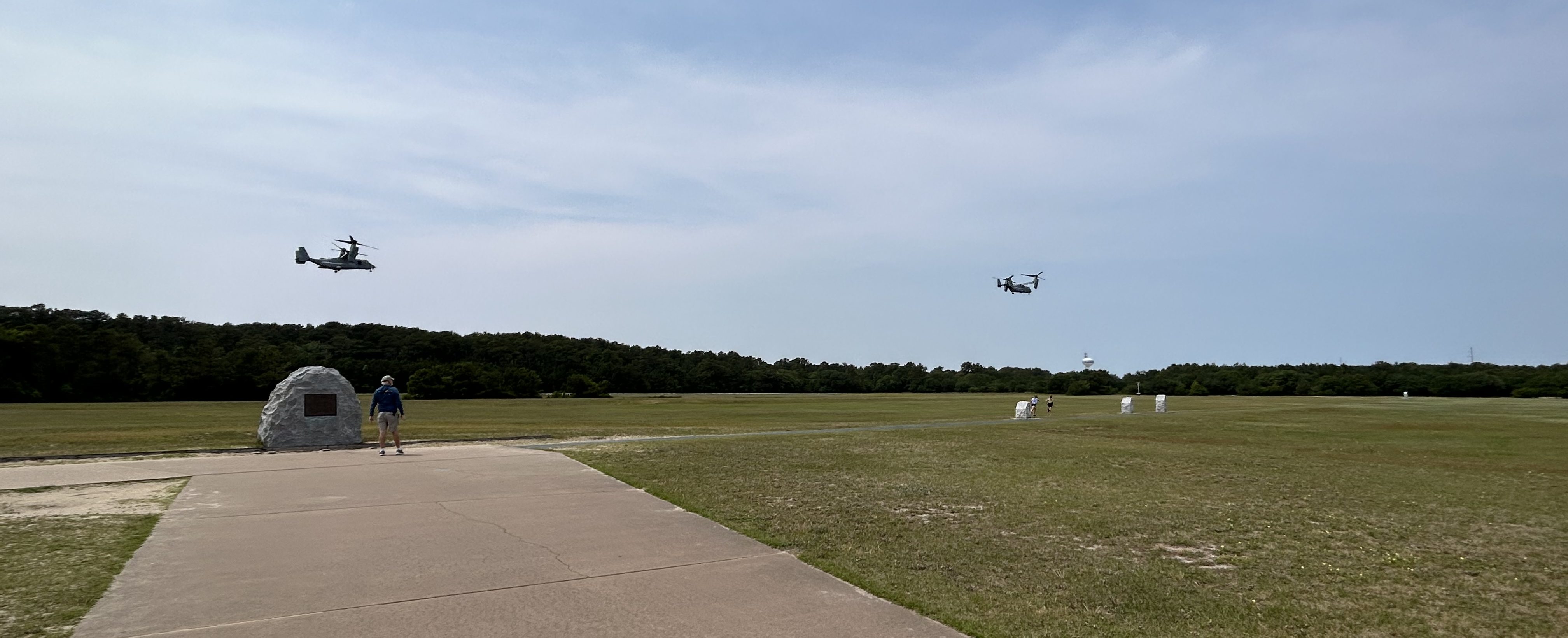

Andersonville, Brices Cross Roads, Camp Nelson, Chattanooga, Forts Donelson, Pulaski and Sumter, Kennesaw Mountain, Mill Springs, Shiloh, Stones River, Tupelo and Vicksburg are Civil War sites. Johnson, Reconstruction, and Tuskegee Institute cover post war struggles. Carter, Sandburg & Wright Brothers are historic highlights. Birmingham Civil Rights & Freedom Riders, Emmett Till, MLK, Medgar Evers, and Tuskegee Airmen reveal the continuing struggle for Civil Rights.

I learned more traveling in the southeast than any other region, as the area is so rich in history and culture. And the preserved natural areas include some of my favorite park experiences, from underwater and underground, to rivers and shores, and to wildlife experiences in mountain forests. And they can all be explored without traveling in a carbon-burning vehicle.