Alaska awaits, but in the meantime, I have visited all 4 National Parks and 16 park units in the Pacific Northwest region, plus 2 heritage areas, 1 affiliate, trails and biospheres. Part of the Manhattan Project NHP is in Washington too.

The four national parks all contain snow capped volcanoes. There are fossil, cave and geologic sites, 3 lake recreation areas, and many fascinating historic sites to enjoy. The region is beautiful, with rugged coastline, forests, mountains and wildlife.

Idaho

- City of Rocks National Reserve

- Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve

- Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument

- Minidoka National Historic Site

- Nez Perce National Historical Park

Oregon

- Crater Lake National Park

- John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

- Lewis and Clark National Historical Park

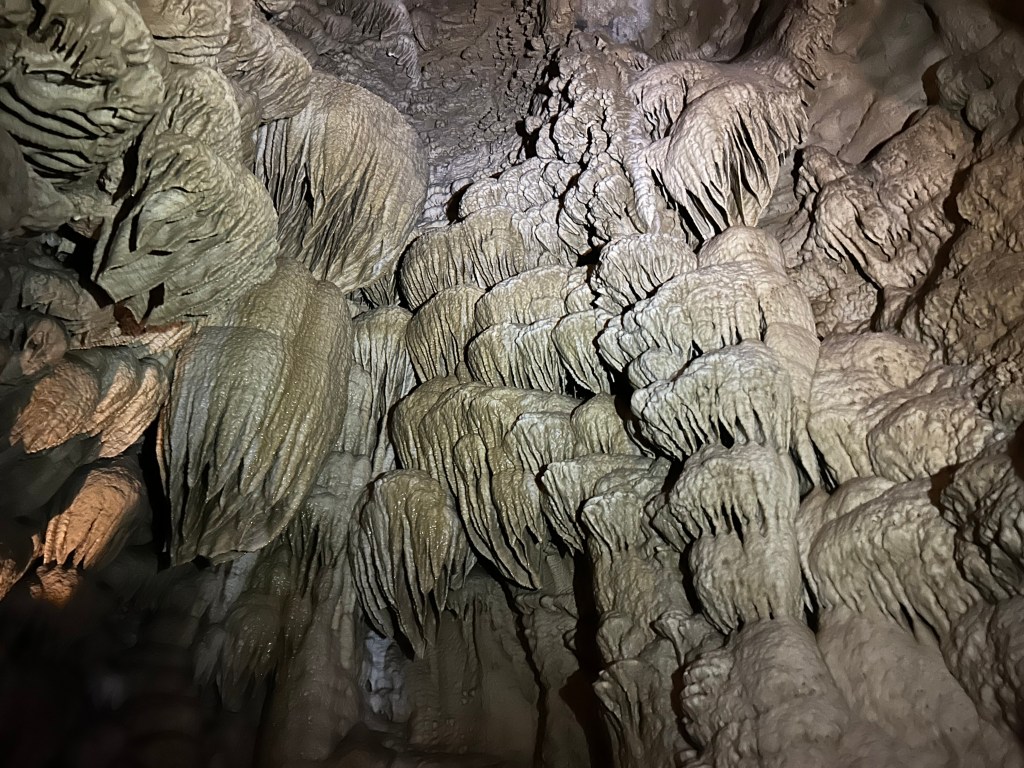

- Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve

Washington

- Ebey’s Landing National Historic Reserve

- Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

- Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

- Lake Chelan National Recreation Area

- Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area

- Mount Rainier National Park (below)

- North Cascades National Park

- Olympic National Park

- Ross Lake National Recreation Area

- San Juan Island National Historical Park

- Whitman Mission National Historic Site

Read my posts, and get out there and enjoy!