The trail is a crime scene, but we must remember, understand, judge and commit ourselves to being better. In the early 1800s, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee (Creek) and Seminole tribes in the southeast were trying to balance their own culture while adapting to new ways of life. Sequoyah had created a Cherokee alphabet by 1821, and many had assimilated into the new communities, often through intermarriage, building homes, farms and businesses alongside immigrant families.

But many voters (at the time white males) had deep racist fear and hatred of Native Americans (and also wanted their land), so they voted for politicians who would remove the tribes. Andrew Jackson had a successful political career, and purchased a plantation and over a hundred slaves to work it. Appointed a colonel in the Tennessee militia, he gained national fame during the War of 1812–an expansionist war of choice against Native Americans and their British backers: “Remember the Raisin”. Jackson led troops including regiments from some of the five ‘civilized tribes’ above in the slaughter at Horseshoe Bend in 1814. One of his soldiers was Sequoyah, who saw first hand how the rebellious ‘Red Sticks’ were cut down by superior weapons. Jackson used the victory to betray his Native American allies by forcing the Muskogee who had fought on both sides to cede almost half of Alabama and much of southern Georgia in the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson.

Within 10 years of Horseshoe Bend, the Chickasaw had ceded 1/2 their territory, along the Mississippi River in western Kentucky and Tennessee (between Shiloh and Fort Donelson), retaining much of northern Mississippi (around Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo). The Choctaw lost their land near Vicksburg, and lived south of the Chickasaw. The Muskogee were restricted to a fraction of their land around Horseshoe Bend in eastern Alabama (around the Freedom Riders Monument). The Seminole had lost around 1/2 of Florida and lived in the swampy center. And the Cherokee still held their land in the mountainous corner of Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee and North Carolina, from Little River Canyon—which became a waypoint on the trail—and Russell Cave—which had been continuously inhabited for 10,000 years—, to Kennesaw Mountain and Chattahoochee River up to Chickamauga and Chattanooga, and up to the Smoky Mountains. (Yes, much of the Civil War was fought over land stolen from natives 50 years earlier).

Jackson is remembered for winning the Battle of New Orleans, but we should also remember the aftermath of the War of 1812, which ended when John Quincy Adams negotiated the Treaty of Ghent. Spanish Florida had been allied with the British, who had forts on the Panhandle. When they withdrew, they gave over one fort to a group of Seminole and African Americans. This became known as the ‘Negro Fort’ which caused great concern among those who benefited from slavery in the southeast. General Jackson sent in forces, and the fort was leveled when a cannonball hit the powder magazine. The Seminole Wars continued for decades, and the history of natives, African Americans and negotiations over Florida is fascinating.

Adams, who supported financial compensation for the five tribes, won a contingent election for President in 1824, but then Jackson defeated Adams overwhelmingly in 1828 and was reelected in 1832. As President, Jackson refused to follow a Supreme Court ruling in favor of the Cherokee, and he supported segregation of natives and both state and federal jurisdiction over native land. Jackson supported and signed the ‘Indian Removal Act’ of 1830, intending to remove the five tribes from their remaining land. Tens of thousands of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muskogee and Seminole were removed from the southeast and relocated to Oklahoma with thousands dying on the forced migration trail: rounded up and held in forts, with few possessions, homes looted, families separated, marched under guard, some in chains, suffering cold and exposure, denied medical help, including women, children and the elderly. Stops along the way included Arkansas Post, Little Rock, Pea Ridge and Fort Smith in Arkansas and Wilson’s Creek in Missouri.

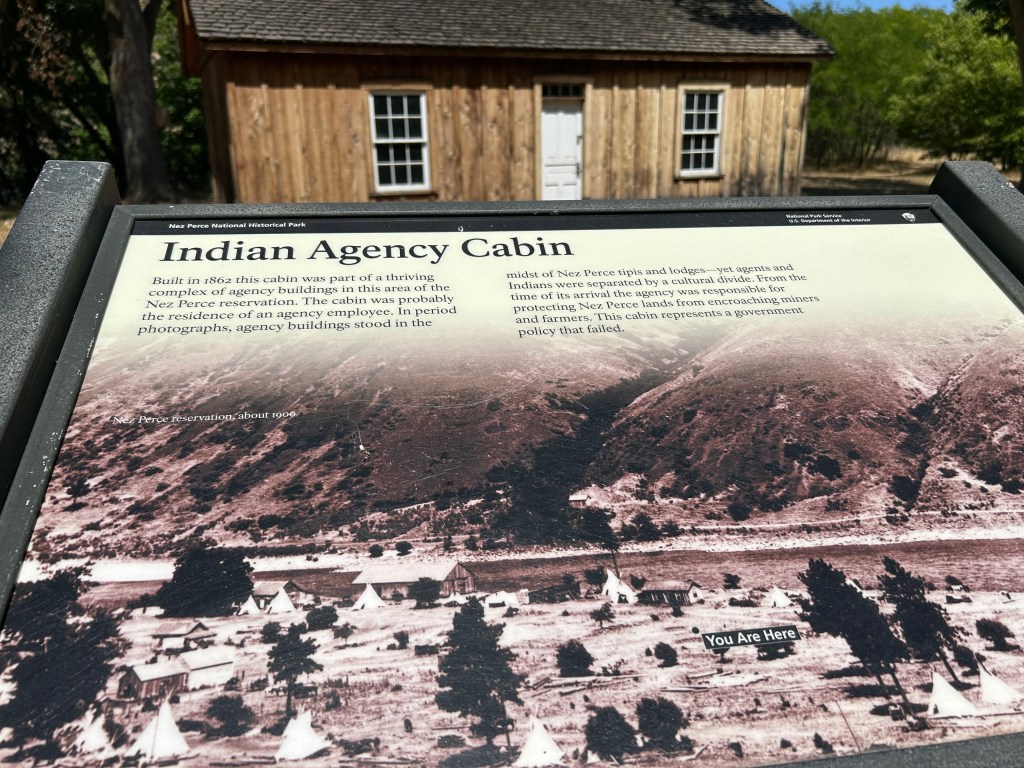

The historic trail focuses on the Cherokee, but the removal act was for all tribes east of the Mississippi. The Chickasaw (see photo above) were able to sell some of their land and moved first. The Choctaw were cheated by treaty but moved too. Many Seminole continued to fight, with some moving to Oklahoma and others to reservations deeper in central Florida. The Muskogee ceded their public land to Alabama, and Jackson refused to defend their private property from being stolen. The rest moved after the Creek War of 1836. The Cherokee also lost their land that year in a treaty their leaders didn’t sign. Jackson used bribery, fraud, intimidation and war to effect the removal. Over 70,000 Native Americans living east of the Mississippi, including the north, were removed under his policies for 8 years and enforced by his Vice President and successor Van Buren.

Some of the Cherokee hid in the mountains, and their descendants still live in towns like Cherokee, on the southern border of Smoky, where you can see signs in Sequoyah’s written language. Eastern Oklahoma territory became tribal reservations for the Cherokee in the north, Chickasaw in the south, Choctaw in the southeast and both Muskogee and Seminole in the middle. Today, the tribes there thrive, have found ways to come to terms with the trail’s brutal history and have chosen to move forward. This is an inspiring example to face the facts, recognize the evil acts and resolve to be better people.