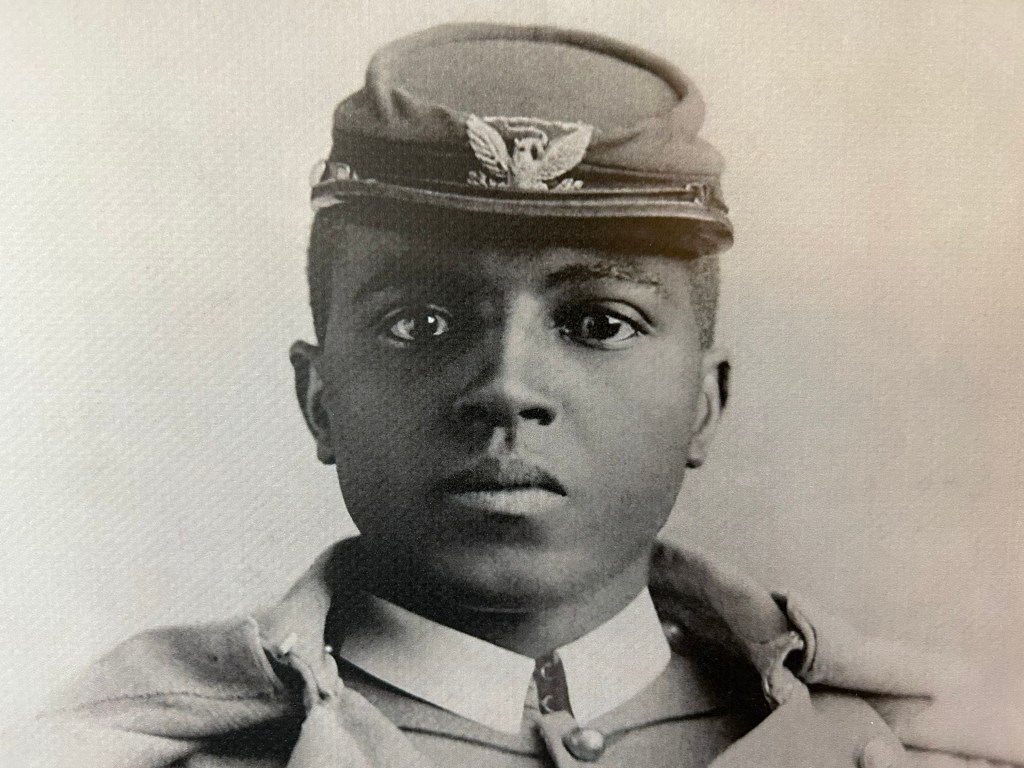

Harriet lived in Auburn—when not on the road—from 1859 until her death in 1913. The photo above recently discovered locally is the youngest one on display here. One local visitor said that his grandmother used to visit her and sit in her lap, and he brought more photos. The long term docent, a Vietnam Vet, used to live in the Tubman house and helped lead the effort to raise money for the restoration. Tubman purchased seven acres here from William Seward, of ‘Seward’s Folly’ fame, and a few of her belongings are on display—including her bed, bible and sewing machine—in the old folks home she managed here.

The park rangers are in town, while the home tours are run by the AME Zion Church, an official park partner. Until the operating agreements are finalized, the partner organization runs the majority of the park with a small devoted staff of around one, and the park service runs the church in town which Harriet attended.

I highly recommend reserving the tour, given at 10 and 2. I believe the docent’s name is Paul Carter, and he is both extremely knowledgeable and an excellent storyteller. For example, many of the visitors had heard about secret messages hidden in quilts that supposedly were used to give directions on the Underground Railroad. But there is little to no evidence of this, and logically it isn’t clear how these messages would have been understood by plantation slaves.

When Harriet was seven, she was spotted eating a cube of sugar, which meant being whipped mercilessly. Instead, she hid for days in a pigsty, fighting for scraps to eat. As a teen she received the head injury which caused a type of epilepsy that she interpreted as giving her visions. This was in Maryland, where she feared being sold down to the Deep South where conditions were much worse.

Keenly aware of the brutality and deadly reality of slavery, she began organizing escapes for herself and her relatives. With support of Abolitionists on the Underground Railroad, she became its most legendary conductor, personally leading 13 missions of hundreds of miles from plantation to Canada on foot, often crossing the border near here, rescuing 70 directly, more indirectly and losing none. She gave away her own money, spoke to Abolitionist groups, and raised money to end slavery. During the Civil War she spied behind enemy lines and led troops into combat rescuing many hundreds more. Later in life she spoke in support of women’s suffrage, with her friends Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony. This iconic American hero stood less than five feet tall, and she more than deserves her place on the $20 bill.

If you hear the dogs, keep going.

Harriet Tubman

If you see the torches in the woods, keep going.

If there’s shouting after you, keep going.

Don’t ever stop. Keep going.

If you want a taste of freedom, keep going.