This UNESCO Biosphere’s most remarkable feature can be seen from space, and you may have wondered about the Eye of Quebec when looking at a map of Canada. Over 200 million years ago a meteor hit here, leaving a 70 mile crater. When the river was dammed for hydropower, the lake in the crater’s ring became permanent with an island in the middle. While it’s possible to drive an electric car up there, I didn’t have a lot of time to hike or kayak around the lake, and, while I support hydropower (with fish ladders), I don’t need to see a dam. I would like to go back to experience Innu culture, but for now I chose to visit the ecologically diverse coastal part of the biosphere.

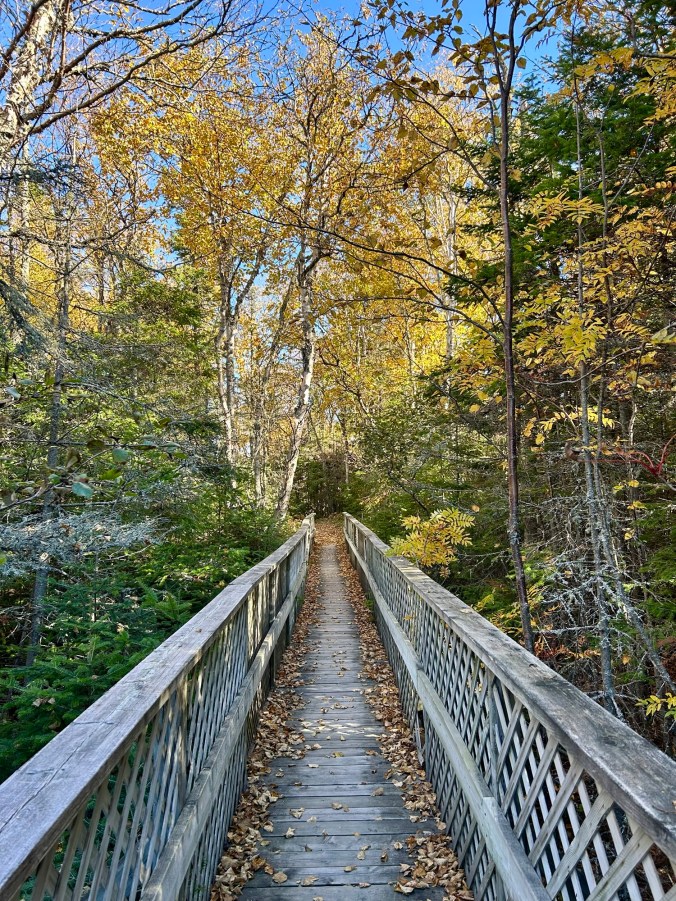

On the drive here, I saw plenty of rivers, waterfalls, foliage and bays, but this is a particularly good place to get a sense of all of the ecosystems in close proximity, especially near the lowlands that are large enough to have subtle differentiation in plants reflecting how many days per year each part of the land is flooded. Between the Manicouagan River that powers the dam and the Outardes River, there is a delta with Outardes Nature Park on its southwest point. Here there’s a fine visitor center, campsite and good trails to see the different boreal forests, salt marshes and dunes. I saw a Cooper’s Hawk, several Black-bellied Plovers, and a Ruby crowned Kinglet, in just a few minutes. It’s a lovely spot.