Our history is replete with racism, and many of my posts are devoted to its tragic examples: US War on Native America, Road to Abolition, Equal Education, Black History and American Concentration Camps. Since genetically all humans are the same species, there is no scientific basis for racism. We are all on the same side. But in my travels, I have found both overt racism and subtler ethnocentrism everywhere. I have heard Swedes make fun of Norwegians, British belittle the Irish, Italians disparage Romani, Turks and Greeks complaining about each other, Russians being anti-Semitic, Japanese discriminating against Koreans, Chinese distrusting Japanese, Malaysians criticizing Chinese, Israelis insulting Palestinians, Tanzanians maligning Arabs, Dominicans faulting Haitians, etc. I’m sure many of the same folks also made negative comments about Americans, behind my back or even calling me a ‘big nose’ or ‘foreign devil’ to my face.

Basically, racism is a damaging and potentially deadly way of thinking about others. Racism divides society, treats people unfairly and often results in violence against innocent people. Academics argue about whether prejudice is an evolved human trait or whether racism is learned. I doubt anyone learns to be racist by reading 19th century books on Phrenology or old Nazi propaganda. People who look up old racist literature have already formed their views. Children acquire racial biases as toddlers and pre-schoolers, often unconsciously by observing adults. Some tribal mistake in our instinctual thinking makes us vulnerable to distrust others, unknown to us, and wish them harm. Tribal unity on superficial facial characteristics may have once been useful in outwitting Neanderthals, but in the modern, interconnected global community, it is not just obsolete, it is a deadly plague, pitting billions against billions, all the same species.

Some academics stress the importance of systemic racism, the structures that sustain it, and the leaders who promote racist ideology. But this logical approach has a human weakness, so a systemic solution is asymmetrical to the problem. Most racist adults deny that they are racist. Relatively few risk public shame with overt racism. Racism lurks in the shadows, until it explodes. Some deplorable adults promote racism consciously, but it is hardly an intellectually rigorous movement. While diversity, equity and inclusion are taught formally, racism spreads informally. In my experience, I’ve heard more racist comments from illiterates and drunks than sober academics. Racism spreads quickly among less educated people who lack access to the benefits of vibrant, integrated multiracial communities. W.E.B. Du Bois exposed the real, blunt view of racists behind their fragile intellectual facade of superiority: “they do not like them”. Racism may be an ideology to a few, but it is an instinctual flaw in many.

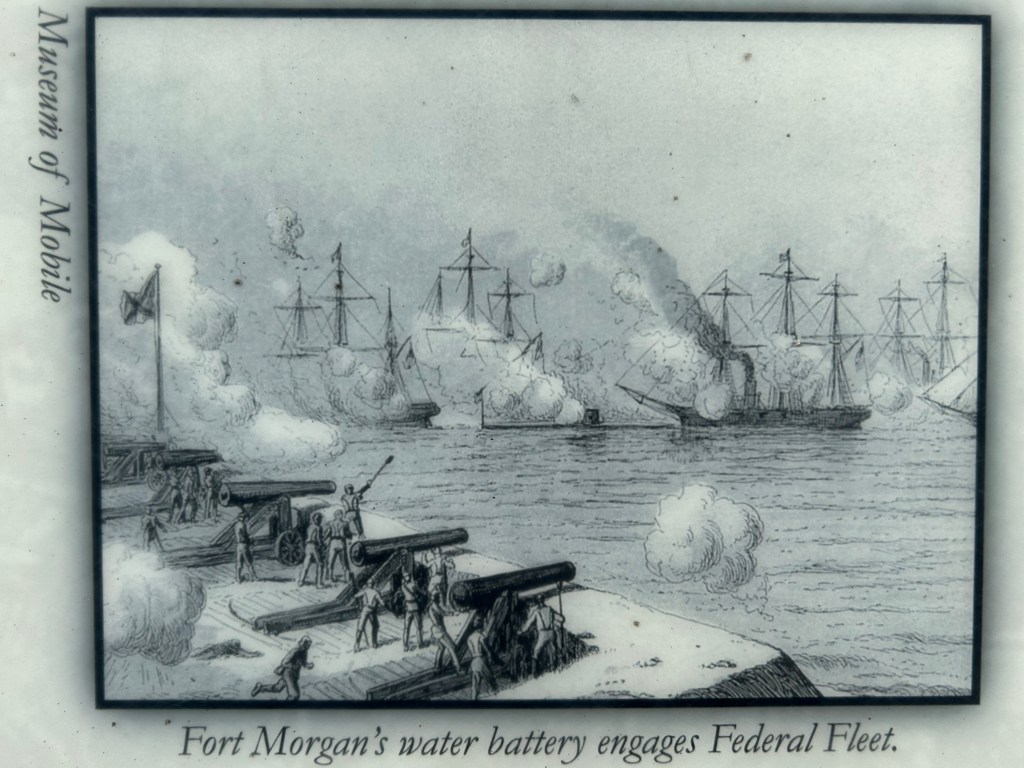

While racism is still obviously employed consciously as an instrument of political power, its mass effectiveness lies in its unconscious appeal. If folks already have deeply rooted prejudices, it is easier to convince them to act cruelly, even without evidence. Missionaries believed they were doing God’s work to take Native American children away from their parents and put them in boarding schools. Soldiers believed false and grossly exaggerated claims that Native Americans had committed blood-thirsty atrocities, before they machine-gunned women, children and the elderly as they slept, before taking fingers as souvenirs. Slave owners believed their superiority gave them the right to use whips and chains for generations. School boards believed that money was better spent on white children. Mobs believed that an unproven allegation of sexual assault justified days of death and destruction. And many believed that Americans of Japanese descent could not remain free, while Americans of German descent could. The cruelest acts were committed by people motivated to act without evidence.

Any system can become an instrument of racial injustice, if it is filled with enough people with deep-seated racist views. A racist jury will rule unjustly, no matter how the law is written. Political leaders do not adopt racist policies because they were proposed by Ivy League think tanks, they adopt them because they are expedient and popular among ignorant people who support them. Columbus did not wait for the King or the Pope to issue racist proclamations before enslaving the first Native Americans he met, because he brought base racism with him and his crew. And they immediately decided to apply it to the Taíno, because they were different. The root cause of centuries of tragic American history is the false, racist assumption that there was something wrong with the other group of humans. Racism is the instinctual mistake within us that causes us to break the Golden Rule.

So, since racism is fundamentally a problem of instinctual thinking, the first step in solving it is to reveal it within ourselves. We all act instinctually, or we would forget to eat and die. We are all emotional, with a million likes and dislikes, preferences and aversions. We mimic, extrapolate and project. We have a physiological and evolved social need to group together, find similar soul mates, and to feel good about ourselves at the expense of others. Our society enforces homogeneity from pre-school. Sesame Street taught us, “one of these things is not like the others, one of these things just doesn’t belong”. But when we defectively apply that instinctual thinking to groups of our fellow humans and feel that someone “just doesn’t belong” in our neighborhood, due to their race or ethnicity, then we are being racist. First, be aware.

Being anti-racist requires honest introspection. If you can find a racist attitude in yourself, understand where it came from, and judge it to be hurtful and wrong, then you can fight it. You can change your words and deeds. And then, you can apply that new skill to the world. Suddenly, you will recognize the next racist thing you hear as racist, and you will have the opportunity to object. You can make a little more effort to understand people who are different, and you might find that you like their food, their humor, music, literature, style, or even some of their religious beliefs. Ultimately, you must apply the same open-minded attitude to all groups of humans.

When I lived abroad, groups of schoolchildren would point at me, giggle and sometimes call me names, because I was foreign to them. Their school uniforms, group behaviors and appearance was equally strange to me, at first, but I was happy that the country stopped burning and beheading foreigners who looked like me some 150 years earlier. Culture shock has two sides, when you fall in love with a culture and when you hate it. Before you really get over culture shock, you need to go through both stages. Then you can stop seeing one group—a single culture—and start seeing the diversity within the group.

The simple truth is that there are good and bad people everywhere, in every group. It is neither accurate nor useful to judge whole groups as good or bad based on superficial characteristics. When groups of people share the same prejudice unconsciously, they begin applying their racism broadly. When groups share prejudice consciously, they organize that racism into a damaging and dangerous force, breaking down a peaceful, fair society, challenging laws and morals, and hurting innocents. Decades later, people may acknowledge that one case was wrong, without admitting that the same instinctual fault still persists.

Isn’t it time for us to admit the full extent of our racism, understand it, and stop it completely? Must we continue to repeat the worst of our history in new ways, for the same old reason? Can’t we finally decide that all humanity deserves to be treated as we believe we should be treated?